The Variable

Ullr Fest has come and gone. The world-record shot ski reclaimed, the bonfire lit. Still, the statue of the Norse god stands motionless at the base of Peak 8, bow drawn, arrow aimed at a widening patch of dirt beneath the Colorado SuperChair. Kids slither around sharks—rocks tucked between moguls—and micro-forests that push up defiantly through what snow persists. Exasperated instructors confiscate skis and send one-footed groups down the greens. In Broomfield, the corporate wizards reach for euphemism: variable, packed powder, early-season conditions. But it isn’t early season. It’s Christmas week—the first peak rush of what’s supposed to be winter.

What’s happening isn’t mysterious. A persistent ridge of high pressure has diverted storm tracks north. Daytime temperatures sit above freezing at base elevation, refreezing weakly at night, if at all. Snowmaking fills narrow wet-bulb windows, laying down dense, artificial ribbons that abrade quickly under holiday traffic. Natural snowfall hasn’t built depth; it sublimates, melts, or compacts back into dirt. Thirty-seven of 193 lifts open. An eighteen-inch base. Winter exists, technically—but unevenly.

“Don’t worry,” D. tells me when I ride the gondola down with him after a day of no lessons. He’s an older instructor, the sort who seems to have been here since wooden skis. Someone I’ve known without really knowing—an enduring presence in the kids’ ski school. “There was a winter like this once, back in the ’80s, before snowmaking. We shut down for a month. Then it dumped. And when it did—we had the biggest spring I can remember.”

The new locker room sits beside the Grand Colorado garage. The hated uphill slog of our old home is memory, replaced by a brand-new basecamp that’s small, poorly ventilated, and short on benches. The laughter and rituals carry over, but our common table is gone. So is the bathroom. Everything feels compressed—a contraction that never names itself as downsizing. We’re seasonal workers in an industry calibrated to weather, and weather has become less reliable.

Back in November, amid the locker-room reorganization, I moved into an unfinished basement room like a fully grown adult child returning home between jobs. Several instructors moonlighted as contractors (or maybe it’s the other way around). They were working to finish the space before the main workforce arrive. Lockers stood loose from the walls. Boot dryers were shoved into a corner, their hoses arcing into nothing. One instructor wielded a drill wearing a sweatshirt from the race camp I attended on Mt. Hood as a kid.

“Where’d you get that?” I ask.

“Oh, I coached there back in the day. A lot of us did. D. founded it.”

The next day, I told D. I was a camper—more than twenty years ago. We traded names and dates. One coach lives in Switzerland now; D. visited him a few summers back. He tells me about building the A-frame cabin where we slept—the steps where my friends and I practiced Britney Spears dance routines. We remembered lunches on the glacier, rafting the Chutes where no kid stayed dry, the end-of-camp cookout. Wandering old-growth forest, sweaty palms linked with boys.

After work, I went to my storage unit and did some personal archaeology. In my hands: a bright purple photo album from my first summer at Hood. Cut-and-paste photos of preteens with raccoon eyes, speed suits paired with shorts, helmets discarded on the glacier. I showed them to D the next morning. He studied my awkward, pubescent face—puka shells, Abercrombie tees—then said, “I remember you. You haven’t changed much.”

I smiled. I remember him too, vaguely—five in the morning, making announcements while we packed sandwiches before piling into the van to ride up to the Magic Mile. We skied only in the mornings; by afternoon the snow was too soft. Then we became regular campers again, heading into Government Camp for huckleberry milkshakes, letters home, sneaking into the snowboard camp to use their PlayStations. Remembering those summers now makes me feel old.

Variable isn’t just a euphemism for bad snow. It’s time. Bodies. Jobs. Infrastructure. The way memory surfaces without warning and returns you to a version of yourself you almost forgot.

The locker room is finished. Blue jackets appear on hooks. Boot dryers hum, filling the air with their familiar musk. Still, the snow doesn’t come. I return from another lower-mountain lesson, sixth toe burning, wearing only a thin base layer beneath my uniform, unsure what the uniform is for.

On the hook of my locker hangs a patch of white: a hoodie from the 1990s. From my old ski camp.

28 hr (1,874 mi) via I-80 W

Ohio

Ski bro at the pump—

Jersey plates, puffy jacket,

knowing nod ensues.

Presidential

Birthplace of Lincoln—

green signs lecture as we drive.

Birthplace of Reagan.

Work Zones

Chevrons flash orange.

Arteries of asphalt squeeze;

neon hazards glow.

Iowa

Turbines rake grey sky.

Billboards preach roadside gospel—

America shrugs.

Accident

Semi on its side,

tipped like a child’s toy truck—

steel guts glint in sun.

Ovid, CO

Metamorphosis:

state lines shift, the earth stays flat—

Nebraska, but not.

MOI

My knees were cold from kneeling in wet November leaves. Someone was playing an unconscious victim with unnerving conviction, half buried in duff. I palpated her limbs the way you check a jacket pocket you’re almost certain you haven’t lost your keys in—half hopeful, half afraid of what you’ll find.

“Just remember,” our instructor called out, hands tucked into his vest pockets, tone dry as tinder, “CPR doesn’t work in the woods. Hurry up and figure out what’s wrong with your patient.”

He wandered over to inspect my technique, which at that moment consisted mostly of wrestling my patient onto a sleeping pad and rooting, somewhat desperately, for a carotid pulse.

“Don’t reach over your patient like that,” he said. “Take the pulse on your side. Otherwise you’ll strangle her.”

Killing my first patient felt like a reasonable beginning to Wilderness First Responder—known, with varying degrees of affection, as “Woofer.”

For ten days, our group of twenty-one strangers revived plastic infants with stiff limbs, treated imaginary drunk campers, and staged the mass-casualty aftermath of a downed gondola in the pines of New Hampshire. Mornings meant rolling out of bunk beds, submitting gratefully to Nancy’s enormous breakfasts—Nancy being the campus cook and, by consensus, the only person keeping the entire operation emotionally solvent—and marching into the cold for scenarios. We memorized the necessary acronyms: AVPU, ABCs, SOAP. But the one that rooted itself most insistently—lodged, really, the way an impaled branch might—was MOI.

Mechanism of injury.

The origin story of pain.

The plot twist that gets you here, cosplaying catastrophe in the woods.

Outdoor professions attract a familiar cohort: the recent graduate not quite ready for a desk, and the retiree who spent twenty years at one and finally suffered the sort of existential rupture that results in a backpack purchase. Because of finances, there is very little in the middle. The twenty-two-year-olds are perfectly content to live under tarps in a state of communal, provisional bliss. The retirees, meanwhile, can afford to resurrect the happiest memories of their youth with the zeal of someone performing chest compressions on nostalgia. The metronome remains the same, but the song used to keep rhythm has shifted—from the Bee Gees to Chappell Roan—leaving those of us with aging but still functional knees and long Zillow wishlists in a kind of generational no-man’s-land.

Around me sat human clippings from a vintage REI catalog: rookie ski patrollers; a seventy-year-old scientist who surveyed remote Alaska; a retired teacher moonlighting with search-and-rescue; a twenty-something backcountry ski guide; a young “brown bear” guide fresh off his summer in the Kenai Peninsula; an eighteen-year-old New Yorker whose motives remained inscrutable; a nature therapist in her sixties. Only two people were in my age bracket. We spotted one another immediately, exchanging the quiet recognition of travelers who’ve missed the last ferry and now occupy the same dimly lit dock.

23 YOF.

70 YOM.

40 YOF.

Even stripped to the barest patient identifiers, we were an earnest, slightly improbable cast—twenty-one strangers who had, in various ways, accepted that the wilderness is where one eventually meets the hard limits of the human body.

“What’s our favorite word?” the instructor asked one morning, tapping the smart board with a digital pen that seemed to please him disproportionately.

“Continuum!” the class replied, as though it were a moral directive.

And in a way, it was. Everything, we learned, exists on a continuum: shock, infection, heat injury, hypothermia, traumatic brain injury—which the instructor colorfully described as “the brain trying to leave the skull through the big hole.” Careers, relationships, and taxes share the same sliding-scale inevitability. Talking nicely and sugar water, we were assured, help with most things.

“At the end of the day,” our instructor announced, “we’re all fucking hummingbirds.”

By then we had practiced impalements, strokes, heart attacks, broken ribs, tourniquets, and death notifications. We stabbed training EpiPens into our thighs and splinted one another’s intact bones with sticks and sleeping pads. Underneath the theatrics pulsed a quieter question: Will I ever need this? And: Will that ever be me?

Last year, it was. I had been a real patient. There is no moulage for c-word things. Nothing in the textbook—despite its generous enthusiasm for diagrams—prepares you for the way a medical event can rearrange your sense of chronology. My MOI was internal, discreet, the sort of plot point you can’t point to on a map.

Pema Chödrön writes that “nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to know.” If that isn’t a continuum, I don’t know what is.

By week’s end, EMT Sensei—his own MOI wrapped neatly in a knee brace—led us to a ridge where five classmates and two mannequins lay strewn in dramatic disarray, moulaged with almost theatrical verve. Moving toward emergency always feels like approaching a mirror: the mountains we climb, the waters we cross, the people we love; the moments when things go wrong and you kneel beside a body, hoping your hands remember their choreography.

“So, what did we learn this week?” he asked on the final day.

“CPR doesn’t work in the woods!” we shouted.

But the unspoken second half had become obvious: But that doesn’t mean we don’t try.

I tucked my badge away and climbed back into the Subaru, pointing myself west. At my cushy resort mountain, is ski patrol. Helicopters on call. An army of elite orthopedic surgeons.

But first responder training isn’t about conquering chaos or even saving lives; it’s about cultivating a kind of interior ballast. The ability to arrive—at accidents, at relationships, at your own life—with a little more steadiness than the day before. To assess scene safety first, then decide whether you have a duty to act. And if you don’t, whether you will act anyway. It’s about widening, however minimally, the fragile circle in which you may be able to make something a little better. Including, it turns out, the slow, awkward business of getting older—especially when you find yourself wedged between the sendy, twenty-year-old hopefuls and the sixty-something wilderness sages. It is, like everything else, a continuum.

In the end, MOI feels less like a mechanism of injury than a mechanism of insight: why we are drawn to these places, why we return, why some of us build our odd little lives at the edge of weather and chance.

And why, in a hexagonal building in New Hampshire, twenty-one strangers worked so intently—earnestly, imperfectly—to learn the simplest and hardest thing: how to keep one another alive.

First Frost

Hoar

Yard sighs, mother-gray;

brittle blades wake silver-spined—

the forest shudders.

Mr. B. B. Says

“Used to be August,”

he sighs of October rime—

“frost’s gone by lunch now.”

Layers

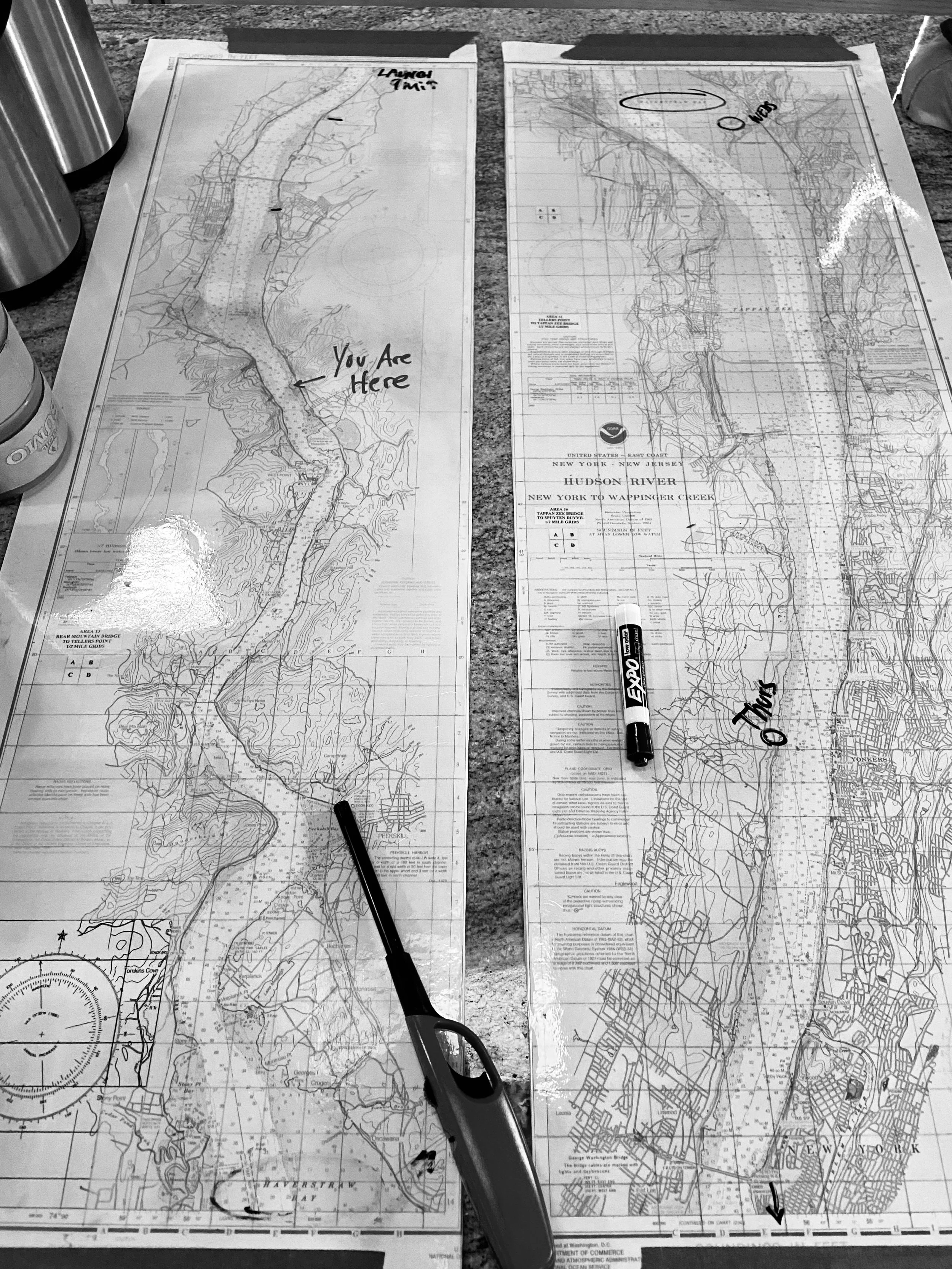

Fog, river’s cashmere;

Hudson layers for the cold—

winter waves hello.

Dry Suit Season

Neoprene to wool—

paddle will soon be ski pole;

make sure zippers close.

Rekindling

Screen door still open;

J lights the woodstove and waits—

embers find their breath.

Denning

Bears nose through the duff;

out back, a tarp snaps in wind—

snow hums in the pines.

On HABs

Spring and fall are bookmarks of brief homecoming. My little farmhouse liberated from Airbnber’s waits for me, tucked in between the toes of New York’s storied hills. More base than home at this point, the sturdy structure built by the hands of neighbors who still dwell on either side of me, up and down the valley, serves for much of the year as gear storage, waypoint, repository of pasts and perhaps-future lives. But in May, a little of June, some of September into November, once again, it’s home.

The whole way down I-95 from Maine, my salt-streaked Delphin snake-strapped to the Subaru’s roof, I’m eager for it. Not just the house with its king size bed with a deliciously firm mattress, but also my so-called homewaters. The Hudson riparian zone flows the warm, familiar brackish where I first slalomed bow-draws through waterlilies that raft in the back-eddies. But before I can even unload the car, a warning from local paddlers lands in my inbox: HABs—harmful algal blooms—on the Hudson.

Kingston Point Beach, my closest and most familiar little launch, is closed.

If the decades of my life are book chapters bound by a crooked a spine, it is the Hudson. Before I was a paddler, the river bookmarked a layer I barely even perceived—an urban wind tunnel in winter, a summer fringe to the High Line, a moat separating “the center of the world” from its antithesis, New Jersey. Then Covid redrew the isobars of my life. I crossed the GW Bridge, followed the estuarine gradient upstream, and settled in the headwater hills the river once carved with ice.

Then, three summers ago, the Hudson became my kayak nursery and classroom: first strokes and wet exits, rescues practiced in green-brown chop, the path that led to my instructor cert with Hudson River Expeditions. My first overnight as a sea kayaker—a seventy-mile, four-day descent from Poughkeepsie to New York—felt like traveling a trophic and cultural cline, the ebb pulling us beneath iconic bridges like beads: Mid-Hudson, Newburgh-Beacon, Bear Mountain, the re-christened Mario Cuomo, and at last the little red lighthouse tucked under the GW. To paddle my way back into midtown was to tie off a transition between life eras with a tidy bowline: from city-bound writer to outdoor professional, strung along a single body of water.

“The Hudson was once a cesspool of filth,” the history-buff kayakers love to remind you. “For centuries, people dumped all kinds of crap here—dioxins, pesticides, raw sewage. Indian Point left its mark, and GE, worst of all, poisoned whole reaches with PCBs. The cleanup only began in the 1970s. Amazing we can even paddle here now.”

The worst outbreak of blooms in 40 years inscribe the present tense in a scientist’s lexicon. Cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton—neither fish nor tree—are photosynthesizers catalogued by color and clade: green, red, brown; diatoms, dinoflagellates, blue-greens. In balance, they underwrite primary productivity, turning light into living carbon. But increase nutrient loading—sewage, lawn runoff, manure; warm the water; slow the flushing—and eutrophication takes hold. Pigments slick the surface like spilled paint. Some blooms merely shade; some produce toxins. All are a message in dissolved oxygen and turbidity: choke the light, starve the gills, tilt the river toward hypoxia. Longer heat stretches stratification; drought reduces turnover; nutrients light the fuse.

It’s not just the Hudson, either. In Maine, they warn of “red tide.” After heavy rainfall, shellfish become suspect. While clams and mussels can purge in days or weeks, oysters bioaccumulate and hold toxins like childhood memories.

Our first weekend back, we drive to Cornwall to meet my paddling buddy, the Wolf. He’s had a birthday since I last saw him at the Seattle airport sitting at a Chinese restaurant in the terminal not quite thawed from our expedition. Seventy-seven Augusts and counting, he now boasts a gold hoop in his left ear and a turkey feather tucked in his hatband. “Talismans,” he calls ‘em, to sanctify his new status as a kayak guide.

Before he ever got the gig, he guided me. We met unloading the same boat, Alchemy Daggers, at Kingston Point, and have paddled together ever since. From Rhode Island to Alaska, the Wolf’s hand-of-godded and towed me out of trouble more times than I care to admit.

This summer, he’s been leading trips Bannerman Castle, the eccentric ruin on Pollepel Island. The HAB index down here isn’t high enough to cancel tours, so he launches our group in the shallows and waves us off the barge wake. Little green dots whirl off my paddle like confetti. A spotted lanternfly touches down on my hat brim—cryptic gray forewings, sudden aposematic red beneath.

“Kill it,” the Wolf says, soft but absolute. “Slowly, if you can, to send a message to the others. They’re very invasive.”

Maine’s erratic lobstermen and postcard beaches give way to New York’s working waterway. Here, paddlers thread wake, wind, and weekend barges. City etiquette seeps upstream—sidewalk habits translated to current and channel. The boats dodge, shift, merge. The tour crowd changes, too—New Yorkers, kin to New Englanders, but tempered: grittier, somehow sleeker. A Women’s History professor from Albany tells me why she drove her family three hours downriver to kayak today: “History,” she says. “What else?”

We cross on slackening flood and scramble over the rocky landing, slick with periphyton. The Hudson doesn’t swing ten feet like Maine waters, but its three-foot tide still breathes diurnally through this fjorded valley. A volunteer guide in a BANNERMAN’S CASTLE shirt with a Long Island lilt gathers us by Mrs. Bannerman’s pie garden. The Wolf hangs back, chewing the inside of his cheek. He knows the script; the island’s story is an American geomorphology of ambition and decay.

“In 1900,” the guide begins, “a Scottish immigrant named Francis Bannerman VI purchased this rock and began building what he called his Arsenal…”

“He was the country’s original arms dealer,” the Wolf whispers, jumping ahead of the official narrative. “Ran the biggest military surplus operation that became the Army Navy Surplus Store. This place is an adult game of hide-and-seek.”

The guide confirms the Wolf’s footnote: after the Spanish–American War, Bannerman bought 90% of the US military’s unused weapons, uniforms, and black powder—so much that Brooklyn officials blanched at the thought of his munitions next door to the naval yard. The baron desired storage and spectacle, so he doodled himself a castle—part Scottish baronial, part billboard—its crenellations spelling BANNERMAN’S ISLAND ARSENAL for every passing steamboat to read. Poured quick and cheap, the concrete fairy-tale went up quick. For a time, it advertised a fast-tracked empire.

Then came the classic Gilded Age parabola: the warehouse exploded in 1920, Bannerman followed soon after, and the slow unspooling began. In 1969, fire set the period at the end of the sentence. What’s left is a buttressed rib cage open to weather, a shell that now stages local theater and a ruin Metro-North commuters know by heart—a concrete pastiche of The Great Gatsby’s closing line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Last year, when my surgery kept us in the Catskills longer than planned, J. became one of those commuters. Three times a week he watched the ruin drift past his train window and wondered, What is that place? Now, circling the bones of its drawbridge by kayak, he carries the gleam of a boy in his first European dungeon. Pattern recognition fires.

“It’s like the AI bros of today,” he muses, and the history professor chuckles. “All in on a good idea, no training or foresight. Hoard the tech, ignore the regs that are coming, pretend obsolescence won’t arrive. I call it the ‘let’s-build-a-fort’ mentality. That’s what this Bannerman dude did—and look what happened.”

“Spot on,” she replies. “Everything that’s happening now is not unprecedented. Only question is: what’s your role in all this going to be?”

The Wolf’s role is clear.

“Four o’clock!” he cries. “Time to go!”

His bow edges out, turkey feather an exclamation point. The historian tracks his line across the channel toward the take-out, reading the microcurrents by the feather. Green freckles wink in our wakes. She flicks a lanternfly from her shoulder; it pinwheels on the miso-colored surface. J.’s comparison lingers. If Bannerman’s boom is a parable for our extractive cycles, the HABs are nature’s bots: cellular networks that, in low abundance, the system metabolizes—but with heat, stagnation, and feed, they scale into systemic risk. Lethal for pets and harmful to humans.

Contamination isn’t dramatic; it’s steady—like sedimentation, a floodplain filling grain by grain. To get rid of the HABs, as the Columbia Riverkeeper says, the task is none other than tackling climate change itself: “…we need to reduce nutrient inputs from industrial chemicals, fertilizers, manure, and human waste; increase water flow; address the temperature impacts of dams; and curb climate change.”

While small efforts from individuals can always help, like picking up pet waste, the true remedy is for it all just to stop. Then wait for as long as it takes for the water to clean itself. But once the bloom is here, there’s little that can be done. Don’t swim in the waters, keep the dog away, and, in time, maybe it’ll dissipate.

“For time is the essential ingredient,” writes Rachel Carson in Silent Spring; “but in the modern world there is no time.”

The next day, J. and I head to the Hudson Valley Garlic Festival. Eighty degrees in late September. Saugerties is a mosaic of garlic hats, witches, vampires, and soil-rich hands. In the hay-bale commons, the Arm-of-the-Sea Theater unfurls a puppet river in cerulean silks and sings a song about photosynthesis to a chorus of equally delighted adults and kids. The troupe’s mission—“handmade theater as an antidote to ubiquitous electronic media and consumer culture”—ripples through the crowd as boos meet the colonial realtor and cheers rise for hemlock, oak, and pine. Some of us are locals; some are not. Everyone is listening. For the finale, the bear waddles onstage with a kayak cinched around his belly, paddle in paw. He dips the blades into imagined current, singing of environmental resilience to papier-mâché trout and city transplants alike.

Tucked in the generous allium bounty of small farms, the play reminds me the Hudson holds more than ruin and warning. Time may be short; creativity is not. New York hope is granular—plankton-small, stitch by stitch—gathering in community theater, in a professor’s silent paddle cadence, in the turkey feather on a 77-year-old guide’s hat.

As sea kayak guides, we lead people into many waters. In Maine we sell clarity—porpoises and ledge ecology, tidal respiration you can feel in your bones. We point to eiders surfing swell, pull out lobster gauges, and say, look how well the world keeps working. It’s easy to forget that Rachel Carson spent her summers on Southport Island, just across the bridge from Boothbay Harbor where I lived this summer—and that her time there shaped the work that helped end DDT’s reign. Without her, the islands where I taught kids to Leave No Trace and delight in shorebird abundance might have read differently. As the history professor reminded us: none of this is unprecedented. The bots aren’t new tech. They’re just the same old contaminants in a new form. Throughout human history, they’ve appeared, accrued, attacked—but they’ve also been diluted, diffused, and defeated.

The Hudson’s lesson isn’t so different. The Wolf threads us through the arteries of an overbuilt watershed to a Gilded-Age folly between interstate bridges. The riparian speaks in closures and neon veils, but also in the older key of resilience and succession: flood-pulse, leaf-drop, Forever Wild. On the banks, a countercurrent slowly gathers—garlic-festival crowds, hay-bale audiences, a bear in a cardboard kayak. Creativity is the Hudson Valley’s unique civic hydrology: it braids strangers, slows the current of despair, and makes room for oxygen.

The river remembers how to heal. We must remember how to belong.

The Spectacles

JUST SHY OF eight, the corn moon lifts over the Sheepscot. Somewhere upstream near Alna sleep the descendants of pines cut for the spars of the USS Constitution, the country’s oldest surviving warship. Downstream, the nearly extinct native Atlantic salmon inch home against the current. Between them, us—two kayakers bookmarked for the night on the edge of the estuary, our REI Penates—stove, sleeping bags, thermoses—set up on an islet known as the Spectacles.

J. and I pass the dromedary of rosé and watch the pale apricot sphere climb beyond the river’s mouth as the tide slides toward its night low. Nine feet of water pull off the ledges like a cloth whisked from an altar. Low water bares the rocky bar that joins the two small islets, the feature that gave this place its name. It’s classic glacial work: granite shoulders rounded by ice, boulder till suturing the halves, cobble glued by crushed shell. Spruces hold the higher ground, wind-flagged by years of nor’easters. Down near the wash, bayberry and sheep laurel dome the edges, and a belt of eelgrass lets go and combs the beach in long green hair.

Our kayaks lie bow-to-bow above the high-tide line. The tent faces east at the northern end; a spruce limb serves as a rack for PFDs, spray skirts, and tow belts. Someone has carved TWO FEATHERS into a dead branch and cinched on a pair of cormorant plumes. Off the eastern shore a sloop anchors for the night. Its mast light and watery reflection shine like two ancient coins suspended in a museum case.

Back on the mainland, long-throated geese arrow south; a rim of crimson edges the maple outside the Boothbay library—living messengers of fall. Breckenridge saw its first dusting yesterday. My hours in this northern latitude stretch toward their end. The click of seasons drives a compulsion to distill the last months into a cohesive narrative. For a skier and paddler, the impulse to arc arises as natural as the geese.

Unable to relax into the moonrise, I break the silence with someone else’s wisdom: “You know, J., kayaking in Maine is special because it gives you intimacy with islands.”

A friend offered this insight earlier this summer. I pass forward as if it were my own.

“Intimacy?” J.’s headlamp confronts me like a cyclops.

“Yep. Spending the night on an uninhabited island isn’t like normal camping. They’re all different, the MITA islands. Their energy, what they give you…it’s a form of intimacy.”

On the rocks below, our border collie noses the periwinkles working the weed lines and the barnacles flexing in the last of the ebb. She returns muddy-pawed and full of tidal-river smells: iodine and sweet rot. She, too, is restless. Comma-splicing at our feet, she scans for seals, who write their script where the moon lays its verse across the watery velum. A gray, blunt-muzzled and big as a buoy, surfaces like a macron, a sight like a long flat sound over the vowel of a small wave. Our collie whines and a loon answers from the black cove. Its one-to-three-note wail—the tremolo—resounds like a dactyl across the scroll of liquid glass.

“So what’s intimacy look like on the Spectacles?” J. grins.

I leave the bait.

“Never mind,” I groan. “Forget I mentioned it.”

I step off our perch, circle to the tent, and shrug into the puffy—the first time since May. I linger with the dark. The thought I dropped finds me again: intimacy. On the Spectacles, it unsettles the eye—apparition or perception, mirror or twin? My own twin answers from a peak 10,000 feet high, calling across corn-flat miles: Snow’s here. When are you coming back? Can it already be time to turn west for winter and slip into my other life? The weather in Maine remains kind; its myriad islands aren’t finished with me yet. I want to stay here. On the Atlantic’s margin, where the tide writes a path and unwrites it, twice a day.

In Book 3 of Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas recounts his long apprenticeship by islands—the Odyssey-esque counterpoint to the mini-Iliad of Book 2. Epics within epics, retold by the losing side: Aeneas is a Trojan, Rome’s mythic ancestor; Homer’s heroes are mostly Greek.

After Troy falls, Aeneas puts to sea in search of a sanctuary: first Thrace (where he cuts down trees for new ships and Polydorus bleeds from the soil), then Delos, sacred to Apollo. The hero misreads the god’s oracle—“seek your ancient mother”—and sets a course for Crete. There, he claims ancestral heritage and the island answers with plague until, in a dream, the Penates correct his course and name Italy as his fated destination. The archipelago continues its syllabus: the Strophades, where the Harpies foul the table and Celaeno curses them to hunger; Actium, where they invent games to discipline fear; Buthrotum, where Aeneas finds Andromache, raw with grief.

For Aeneas, the sea becomes a page and omens his pen. Island by island—punctuated by waves, bound by current—he rewrites his story. It takes seven long years of wandering.

In August, I dreamed a katabasis. I visited the River Styx the way tourists visit Rome: gift shops, a ferry terminal, the buzzy public rush of famous monuments—and, most memorable, waking with the sensation of a cold hand in mine.

Morning rationalized. I led a group of six to Burnt Island Lighthouse and back, pointing out osprey nests and cormorants drying their wings.

A few days later, over Labor Day weekend, I took J.’s family kayak camping. We launched late to evade the rain. Stars lifted on the orange-blazed horizon by the time we were ready for dinner. Kneeling on a granite slab to thread a canister onto the stove line, I felt the phone hum in my back pocket. A message from Japan.

“I am sorry to write with sad news,” my cousin said through Google Translate. “My father, your uncle, has died. We cremated him last week.”

The next morning, there was no more news from Japan. I slipped from the tent before the others and boiled water for tea and oatmeal—a small, solemn meal offered to the dead. Light spilled from the east, and the tears came. For a moment grief caught, then passed.

We slid our keels into the flood and hopped island to island along the outer edge of the bay. We ate lunch on Black, where a yellow-and-blue lobster buoy had washed ashore, Sharpied with a blunt oracle: REAP WHAT YOU SOW.

J.’s father’s partner asked if she could keep the buoy, wanting to take it home as a coastal keepsake.

“I’m afraid not,” I said, thinking of karma and Tokyo. “Technically you’re supposed to turn them in.”

“Hey, can we go to that island next?” J. asked, changing the subject.

He pointed to a dark sickle on the horizon, Wreck Island. The name is literal: a late-summer storm in the 1500s, a ship on the ledge, cries the locals heard and—by law’s perverse permission—ignored. Salvage only if no survivors. Winter smothered the cries until spring’s silence licensed the pillage. Not all place-names instruct; some indict. Locals say you can still hear the ghosts howl in the throat of a gale.

What do you reap if you sow nothing?

Leave No Trace ethics are as anti-Roman as can be. Try to be good guests, not founders. Land and launch toward invisibility. Pitch above the wrack on durable ground; keep off the lichens. Cook on a stove, skip fires unless allowed—and then keep them small and erased. Pack out everything: food scraps, dog waste, tea leaves, and on thin-soiled islands, human waste too. Keep voices low after dark. Give wildlife room; birds and seals own the shore before we do.

Conquest and conservation cannot coexist. And yet, Virgil’s epic, like Homer’s, endures as a work of western literary genius precisely because, somehow, through writing, it overlaps them anyway.

The two feathers are someone else’s marginalia in Spectacle island’s manuscript. Or are they quills—reminders that there are multiple ways of writing and reading, of leaving something behind for others to interpret? A carving is not a colony, but it also not nothing. What about a poem? A cousin grieving half a world away?

We did not take the buoy. Nor did we make for Wreck. We turned around. Part of island literacy is knowing when silence isn’t yours to enter. I felt the pull—the old heroic shape, the easy narrative of confronting the unknown and coming home with a lesson pinned to the mast—but the learning here was different: not everything wants or requires pilgrimage. Turning back is often just as good a reading.

As we pivoted, three gray seals rose around us, big and deliberate. One rolled a shoulder and showed a pale map of scars. Another clapped the surface—a sound like an oar slap. The third thrashed after a mackerel with a great splash. I thought of my dream and my cousin’s message. My mother was the youngest of three. With the passing of my uncle, the middle brother, the postwar generation of siblings is gone.

If Virgil were writing this, my kayak would capsize and I’d meet a sea god riding a seal’s back who’d speak in a voice thick with grief and command. This Maine Sea Lord would address me the way Apollo spoke to Aeneas at Delos, with the confidence only deities can muster: “Seek out your ancient mother,” remember? That oracle is so Freudian it can only invite mistakes. Nothing good comes of chasing an absent mother. For Aeneas, that meant setting a course for Crete, and the island rewarded his misreading with a plague.

But Virgil’s not writing this essay. I am. And even though I studied Classics in graduate school, I am not an ancient Roman. I do not get gods—maybe, now and then, a little bit of kami. If I’m lucky, I get cold hands, constellated skies, no cell service for a few days, and animals that watch closely and need nothing from me. Like memories, they surface long enough to be recognized, then left well alone.

Why do people paddle out to islands?

We give these islands our time, sweat, salt, love, attention. They give us a living grammar. A windline becomes an audience; a fogbank, an argument you shouldn’t force; a name like Wreck, not a dare but a boundary to be respected. Prophecy, closure, visitation, omen—it’s all the quiet feeling of being very close to the world in a vernacular only you can understand.

We are not Trojans exiled from a demolished city, goaded by inklings of destiny. And yet, we are goaded by something. Two feathers. An oracular buoy. A good story.

You are not yet done with the sea, explains my mountain twin to me. You come for the small, accruing knowings: which mossy flat cushions a root; that an onshore breeze will snuff the stove unless you turn its mouth a few degrees leeward and shield with a pot lid. For the field-marks that make a place become itself: the late-season tern that should have already gone, the single monarch angling south over salt, the way eelgrass stains your hands sweet-green.

As 21st-century island-farers, we strive to be better guests. To leave no trace, but maybe take home a learning. An essay. A story. The deeper flow of this narrative is still Virgil’s, translated across millennia to a humbler register for a less heroic age. For that is what good epic poetry does. It conveys the legacy of human saga, great and small, allowing it to be repurposed and contextualized, long after the empire has fallen. The ruins of Aeneas’ heirs attract millions as they decay. The trees of Thrace and Alna—felled for the ships that carry the stories—meanwhile have grown and grown.

Whether the Mediterranean or the Gulf of Maine, seafaring adventures teach human beings to read the world as a text, but caution of arriving at any fixed point of interpretation and anchoring there too long. Scylla and Charbydis remain hazards as real today’s sea kayakers as they were to antiquity’s sailors. The hydraulics of minds and river confluences will always hold the power to swallow a boat whole. Ancient epic’s register can still give us a vocabulary for charting modern meaning. An uncle dies in Japan; a sea kayaking niece on an island in Maine mourns. A seal is not a mother, but also not not her, for the feeling this sighting conveys. Aeneas misreads Delos; Crete corrects him. At Strophades the Harpies make a lesson out of hunger: you will mistake want for destiny until you know the difference in your bones. At Actium, courage becomes ritual. In Buthrotum, grief becomes a craft Andromache lives. The archipelago teaches the threshold—sandbars that appear and vanish with the tides, doubles that are mirror and not twin, moons that look like prophecy but also simply illumine the life that is already there.

Back on the Spectacles, the September morning arrives diluted, the color of milk left in a cereal bowl. The corn moon loosens into it and disappears. Lobstermen work the channel in tight circles, haulers clacking, diesel thrum low in the chest. A gull drops a quahog on a rock and misses; on the second try it scores; the shell shatters clean and neat, a violence that is purely practical. On the sloop, two figures in sweaters step out with mugs and give us the small nod of morning boats. We answer with our spoons, lifted from the oatmeal pot.

We break camp without speaking much. Drybags slot into their hatches; our collie leaps like Palinurus to the bow, and the tow belt clicks back around my waist. J. walks down to the boat, carrying a stick. The dog’s tail immediately begins to swoosh. She leaps off the boat and re-muddies her paws. She’s ready to stay here and play fetch in the intertidal zone forever.

“Hey,” he says. Let’s take just this one, for her. We’ll start a stick library. She loves it here so much…she’s explored every inch of this place. I get it now. Intimacy with the island.”

The bar is already taking water; the path becomes a darker seam and then only memory. One island becomes two again—tidy, divisible. I dip a blade. We slip past the last granite shoulder into the channel, where the river’s cold meets the bay’s salt and stitches a line you can feel with your knees. Behind us, the Spectacles regard us the way a good poet does when you read their work not by luck but by practice: not praise exactly, but recognition.

Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by Scott McGill and Susannah Wright, introduction by Emily Wilson, W. W. Norton & Company, 2025.

Marine Forecast

Weather

Gale warning offshore;

complex low keeps on turning

somewhere off Greenland.

Wind

South wind to ten knots—

rain with gusts up to thirty;

seas six to ten feet.

Small Craft Advisory

Another cold front

tightens over the waters—

small craft have been warned.

Fog

Southerlies rising;

patch fog after midnight—

showers at daybreak.

Pressure

High pressure building

behind the pushing cold front—

seas around two feet.

Fetch / Swell

Fetch laid to the east;

swell wraps around Monhegan,

the storm still speaking.

Muscongus Metamorphoses

ON THE EAST side of the island, the girls are circled on the schist, playing a game they call Silent Football. All but one. A curly-haired camper in a giant sweatshirt lingers out of sight. With her long stick-legs poking from the hem and a mop of honey-colored hair, she looks less like a child than a cria, a young alpaca. At dinner, while we spooned out sticky skeins of over-boiled spaghetti, she whispered something to a counselor and then vanished back to her tent.

The tide drops, and I recall another gathering of girls on this same stone, a little older than this group. Their silhouettes bent in a half-circle against the dark, voices carrying the ritual debrief helmed by the Leader of the Day. To soften the agenda, she decreed each girl claim a “spirit animal.”

“Lemur.” “Gazelle.” “Penguin.”

My co-guide, soft-spoken and bearded, was christened Panda. Sensing his unease, they quickly revised him into Owl. When they reached me, they chose Arctic fox. Perhaps they recognized some intuition of winter in me.

Now, a few weeks later, Muscongus Bay’s horizon again glows pastel. The sky is awash in the candy-colored gradients of Lisa Frank Trapper Keepers, which were still in vogue when I was their age: tie-dyed seas, hot-pink leopards, dolphins leaping from galaxies of glitter. Those binders were Ovidian portals reimagined for the late ’80s—open one and you tumbled into another cosmos. So too here, on an island briefly inhabited only by women and girls, the veil of ordinary time lifts. Without phones, female adolescence reverts to its ancient rites: hair braided into ropes, songs composed, dances rehearsed for the end-of-camp recital. Watching them, I feel as though I am leafing through an illuminated manuscript of my own eighth-grade summer, each page preserving a transformation caught mid-gesture.

The Game Master appoints N., the group’s 22-year-old trip leader, to start the fwap—a pat on the thigh that sends the invisible football spinning left or right. N. is Australian, hair freshly shorn, grin wide, eyes softened with a koala’s solemn playfulness. They tell me how their parents were more concerned with them coming to the U.S. for the summer than going to Africa. They describe a cautionary metamorphosis as temporary as an ESTA visa: “I grew out my hair before coming here,” they recount. “Wore hot-pink Juicy Couture on the plane. Customs didn’t blink. The first thing I did when I got to the camp was cut it all off again.”

The Koala does not know the rules. Neither do I, but I join anyway, alongside my counterpart, M.—a kayak guide-in-training on the edge of her first semester as a high school teacher. She has already memorized all ten girls’ names while I still fumble. She radiates an effortless empathy, connecting with the ease of mythic figures who could charm beasts and gods alike. In my Lisa Frank menagerie, she is the Unicorn—surefooted, luminous, prancing through neon stars. She knows all the rules.

The Game Master intones: “Above all, players must be silent. No student may speak, smile, or show teeth. Permission to speak must be granted by the Game Master. To ask a question, you must raise one hand, cover your mouth with the other, and say, ‘Mr. Game Master, Sir?’”

The fwapping begins. The Unicorn flows effortlessly. The Koala giggles and breaks the spell.

“Mr. Game Master, Sir?” cries one girl through lip-lidded teeth. “The Koala laughed.”

The circle convulses in pantomimed glee. Votes condemn the Koala to further laughter. Democracy and its parody entwine. We play until the sky deepens into purples and electric blues, a neon-coral afterglow burning behind silhouettes of pine. The air shimmers not with rainbow dolphins but with mosquitoes rising in clouds, as if the night itself were sloughing one skin for another.

At last, the Game Master calls it. Teeth flash, sighs escape. The night is promised now to whispered confidences between nylon walls that do not muffle sound. An hour later, around nine-thirty, the three counselors patrol with beams of light and a comforting crunch of dry leaves. I circumnavigate the site, then return to my tent pitched on a northwest outcropping of grey schist marbled white—the sort of surreal geology Lisa Frank herself might have dreamed.

I crawl into my sleeping bag with my book about rivers. While I read of the Valley of the Eagles bifurcating the Mutehekau Shipu in northeastern Quebec, outside, the bay hums with islands. Macfarlane writes, “Spring becomes stream becomes river, and all three seek the sea.” The sea just outside my tent keeps seeking itself. It’s fallen almost ten feet, exposing inshore lobsters scuttling ever closer to the surface. Soft-bodied from a recent molt, they creep from their cast-off shells, tender and luminous until the armor hardens again.

Ovid would know this hour as Macfarlane knows his rivers: when forms seem to slip, and the mind is stirred to speak of new shapes. Myth seeps into real moments, and the ordinary is already in the act of becoming otherwise. I tell myself all is well. The Cria is safe. And yet, as sleep pulls me under, I wonder if hidden in that tent is no longer a shy girl in a sweatshirt, but some liminal creature of the night, eyes startled and luminous in the dark.

To be a sea kayaker is to apprentice yourself to catastrophe. A cosplayer of shipwrecks. We rehearse rescues with the precision of battle reenactors, parsing choreography as if survival depended on it—which, of course, it might. We debate endlessly: should the swimmer seize the toggle or the deckline? Should the towline be clipped gate-up or gate-down? Should a capsized boat be emptied before it is righted, or heaved dripping across the rescuer’s skirt? Even our vocabulary is contested. Is the person in the water a swimmer (neutral), a victim (tinged with pity), a casualty (too severe)? The older the paddler, the harsher the term.

To paddle the ocean is to be drawn into the mythology of disaster. On rivers, dangers are obvious—holes that gulp and gargle, strainers lying in wait, rocks greedy for a snag. But at sea, danger is diffuse, infinite, invisible: storms that consume whole fleets, creatures terrifyingly antithetical to Lisa Frank fantasy—white sharks, tidal bores, flesh-eating bacteria. Sea paddlers scull the threshold of myth itself.

And so, like actors in Greek tragedy, we rehearse our dramas in the amphitheaters of bays and coves before a bemused audience of gulls. We cast our friends as victims and point them toward the foaming rocks: “Capsize there, please!” We rescue, tow, re-rescue. We debrief over whisky, parsing seconds saved, gestures corrected, the chorus of our mistakes echoing back. We tell ourselves we hope these skills are never needed. But deep down, in the ego’s secret Trapper Keeper, we long for the test—that the wild will rise, and we will answer it. With flying Lisa Frank colors.

Later that night: a whisper at my tent.

“It’s me,” says the Unicorn. “The Cria’s sick.”

I follow her into the dark. The moon is a mere crescent, offering no help. Stars blaze above the white pines, their branches pointing skyward like fingers toward the Milky Way. Four tents glow faintly. Three are sealed tight; one yawns open. Around it huddle the counselors like anxious sentries: the Koala, the Game Master, and another, tall and shifting on one leg, a Heron in her blue-grey fleece.

The Cria shivers at the center. Gone is her oversized sweatshirt; she wears only swimsuit bottoms and a thin ribbed tank. Her skin burns, fluorescent with fever. Words rise unbidden—appendicitis, hospital—as fear tie-dyes the counselors’ faces. For all their competence, they are barely older than the campers themselves. The Unicorn is not yet thirty. I, deep into my thirties, am suddenly the elder here.

As we scramble for contact with the mainland, I already know what the oracles have decided.

We launch close to midnight. Dead low tide. The Cria hunches in the bow of a tandem, the Heron at the stern. The Koala fidgets in their single. I raft everyone together and clip on my towline, belted tight at my waist. Above, the Pleiades cluster faintly—or perhaps I only constellate the stars so, needing their sisterly symbolism to steady my forward stroke. On shore, the Unicorn and the Game Master stand hapless, their headlamps the last twin beacons of land. Then they are gone, swallowed by the island’s shadow.

Darkness closes in. I am floating in its midst, small and alone. Do the girls tethered to my boat feel my fear humming through the line like an umbilical cord? For a moment, we drift in tidal nothingness. I remind myself: you are trained. You know what to do.

I paddle. The darkness persists. My headlamp reveals only a few feet of water at a time. Another stroke, long and quiet. Then another. At last, an outline of earth returns. The weight of three laden boats drags me back, but I fold it into cadence. The sky explodes. Stars mirror on the black sea like disco lights on a roller rink. My yellow blades flash gold in the beam of my lamp: wings. In that instant, the Arctic fox dissolves. I become Pegasus. The girls I tow are my chariot.

We glide past tide-born rocks. Crowned like naiads in rockweed, they urge us on. As we near the marina, the talisman appears. We all see her at once, weaving deftly among the sunken traps.

“Oh! Look! A lobster!” cries the Heron.

She scuttles across the sand, separated from us by only a few watery inches of crystalline fulcrum. Her V-notched tail flicks and flashes her onward. Female, armored, ancient—immortal in theory, doomed only by the labor of endless molting. She embodies what Ovid could not see: that metamorphosis is not linear, one body fixed into another. Like girls’ adolescence, it is a continual process of becoming and unbecoming. Tidal, protean, infinite.

And just like that, we have come through the portal. The sea equalizes time, gathering all in its molting myth.

By dawn, the Cria’s appendix is declared safe. She rests on antibiotics and fluids, her fever breaking. I collapse for a few hours in the backseat of my car, then wake to lobstermen hauling traps—men already hours deep in their labor, backs bent, ropes and buoys slick with brine. When I paddle back to the island, the bay has reverted. The rocks that rose like naiads in the night have sunk beneath the tide. What remains is only the memory, filed in the Lisa Frank binder of the mind, its pages still shimmering with otherworldly glitter.

The Unicorn has shrugged off her rainbow mane to become my friend and coworker again. M. sits crosslegged on the rocks before the stove, rubbing her eyes while boiling water for oatmeal and coffee.

“Hey,” she greets me.

“Hey.”

The Argonauts once felled pines to cut their first ships, and with those hulls carved the Greeks’ first great sea story, the Argonautica. To paddle the ocean is to do the same: to hew experience from the deep and carry it back to land as story. The river, like the mountain, has its rhythm—an immediate, urgent narrative pulled by gravity. But the ocean, with its vastness and tides, resists such straight lines. It is the realm of crossings, of epics, of prehistoric species in which the females—protected by laws they did not write—can, in theory, live forever. Ever since humanity began inscribing stories, seafaring has repeated itself, molting like a lobster’s shell. Sailors relive them until, exhausted, they sink back into myth.

Wildlife Tour

Pemaquid Point

Where two worlds once met—

stone hearths, shell heaps, storming tides.

Still, the light endures.

Seals

Pod beached on the ledge;

one swims up like he owns us—

the ambassador.

Great Whites

Eyes scan the water;

“Not common around here,” then—

Sharktivity pings.

Porpoises

Pinniped breath nears,

circling bright-eyed kayakers—

click-magic captured.

Birds of Prey

Osprey! And eagle!

We point out nests like they’re ours.

The birds just ignore.

Cormorant

Deep-diving swimmer—

Darwin gave up airborne bones

for fishing prowess.

Puffins

Will we see puffins?

Nope. Maybe a guillemot.

Definitely gulls.

Terns

Tiny sky scissors—

one lifetime’s flight slowly cuts

a path to the moon.

Lion’s Mane

Flame without a heart;

invertebrate from away,

ghost beneath my boat.

Whales

Minke, humpback, right—

hunted where tourists now glide,

they still sing offshore.

Accidental Birder

It’s said that all paddlers become accidental birders. The ocean makes one by necessity. You move through the places where birds feed, nest, and migrate. When you spend seven days a week on the water, you learn the grammar of silhouettes quickly: the quick dagger of a tern, the buoyant bounce of an eider, the prehistoric patience of a great blue heron stalking eelgrass flats. The bay becomes a kind of page, the birds the marginalia. Eventually, you stop identifying species and start cataloging behaviors—circle, hover, plunge, wait—as if memorizing an unwritten manual everyone else already knows.

When I first came to Maine, I knew birds the way I knew constellations—vaguely, romantically, without understanding. They were background: white flashes in the cove, silhouettes above the fog line. But guiding recalibrates the senses. You start by reading wind and tide, and then—almost without noticing—you begin reading wings.

Like anyone new to the Midcoast, I began with Atlantic puffins—clown-faced emissaries of the North Atlantic, beloved for their improbable flight and perpetually startled gaze. Their colony on Eastern Egg Rock is the southernmost in the world, resurrected through decades of careful conservation.

But devotion shifts. And by July, mine had shifted to the terns.

Terns are built like exclamation marks and behave like they invented airspace. Slender, fork-tailed, bright as chipped porcelain, they fling themselves across the sky with a kind of weaponized precision. Their cry—kee-arr!—has all the charm of an alarm system and none of the restraint. They navigate the world as if the rest of us are simply in their way, which, to be fair, we are. In their lifetimes, they log enough miles to reach the moon and back. The Arctic tern is the world’s longest migrator. For a seasonal human who was itinerant long before she was a guide, the temptation to anthropomorphize is obvious—though the terns, to their credit, would never approve.

Still, the everyday residents held me too: the black guillemot with lipstick-red feet nesting deep in granite seams; the double-crested cormorant drying its waterlogged feathers—the only seabird that never fully repels water; the osprey’s unhurried hunt and that electric cry slicing fog. The nest I point out on every harbor tour—balanced high on a mast—has rendered the boat unsailable for the season, protected by law and by the birds’ sheer obstinacy.

And at low tide in the inner harbor, the snowy egret performs the opposite act: absolute stillness, vibrating at a frequency just beyond human impatience. Her black legs end in yellow “golden slippers,” an evolutionary lure she uses to stir prey from the mud. She moves with the precision of something attuned entirely to tide, not spectacle.

Then there are the gulls—loud, declarative, impossible to ignore—ricocheting off pilings and rooftops. Herring and laughing gulls quarrel over bait scraps with the operatic confidence of creatures convinced the entire coast is their personal franchise.

Some birds reveal themselves slowly; some only at low tide; some not at all. And then, sometimes, a single egret standing in a minus-nine-foot harbor becomes the entire evening—white, patient, unimpressed—stepping through the lavender sunset as if nothing else exists, least of all us.

Lord of the Flies-ing

THE PERIWINKLE VAN bumps up the gravel drive, fifteen minutes behind schedule and looking as if it’s been retired from at least two earlier centuries. With its fading block letters and boxy frame, it belongs to the taxonomy of vehicles that once ferried public-school kids to zoos and municipal pools—the era of discmans, Goosebumps books, and forced proximity. Ten middle-schoolers spill out: nine boys and one girl whose posture suggests that her attendance is compulsory. Their teachers follow—three adults with the slack-jawed fatigue of June.

“The drive,” the kids report immediately, “was like twice as long because the AC didn’t work.”

I remember those rides well: the recycled air, the awkward geometry of growing limbs in a too-small space, a single cassette tape of 70s rock on loop, the sense that discomfort was part of the curriculum. It is faintly hopeful to discover that some rough edges have survived into the age of AirTags.

The group’s leader—a cheerful history teacher—appears with a box of donuts, an unspoken apology for what he is about to unleash.

The Maine air greets the Boston students with an assertiveness they don’t yet have language for. Salt, kelp, lobster tanks, a nearby shellfish farm—all of it collides with their metropolitan assumptions. They ask for a bathroom and are directed to a port-a-potty that, miraculously, smells better than the waterfront around them. Above the kayak shop, a warehouse hums with pumps and filters, tending to thousands of growing clams. Gulls wheel overhead; lobster traps stack like a vernacular archive.

Three days and two nights of kayak-camping lie ahead. My boss and his wife spent the previous evening packing meals into labeled sacks; the group gear—tents, pads, boats, wetsuits, PFDs—is lined up with ceremonial order on the beach. This is their end-of-the-year rite: the urban field trip rewritten for the tidal zone.

After introductions, the lone girl makes a beeline for me. She wears a petunia-colored rain jacket and an expression wavering between indignation and dread.

“I’m Em,” she says. “As you may have noticed, I’m the only girl here. My two friends bailed. I don’t know any of these boys, and I’ve never kayaked or camped before. I don’t want to be here.”

I open my mouth to reassure her but the machinery of group travel intervenes. The luggage erupts from the van: wheeled suitcases, expedition-sized backpacks, a vintage L.L. Bean sleeping bag packed at the insistence of a nostalgic father. My boss gestures toward the red twenty-liter drybags. “Everything you brought needs to fit in these.”

A pause—brief arithmetic—then compliance. Even the boy with the heirloom sleeping bag relents and accepts a lightweight loaner. It turns out air travel has prepared them well: the distinction between essentials and indulgences.

Then comes the real crisis: the history teacher announces that phones must be surrendered.

The freeze is immediate. These are less objects than organs—the central nervous system of their social lives. Still, one by one, they hand them over. All except Em. She stands by the kayak trailer, clutching hers.

“Okay, Em,” I say gently. “Time to hand it over.”

She places it in my palm, fingers lingering a beat too long.

“Great,” she groans. “We’re Lord-of-the-Flies-ing it.”

Once on the water, my boss calls out, “Muscongus means ‘fishing place’ in Abenaki.” The word’s sonorous weight holds their attention for a moment before paddling takes over again. Tandem kayaks wobble and drift like siblings learning to share space.

But the name stays in the air along with the layered reality of the place: two rivers feeding the estuary; lobsters molting beneath us; terns circling overhead; seals surfacing with whiskered appraisal.

“Will we see dolphins?” the kids ask.

“Maybe porpoises,” he says. “They’re like little dolphins. But you need to be lucky.”

He continues with the short history—Algonquian travel routes, George Weymouth’s 1605 landing, the colonists who felled forests and introduced sheep. The kids lean back, half listening, wholly elsewhere: absorbed by tide, texture, the mechanical strangeness of the boats.

Em paddles with D., a quiet boy in a T-shirt featuring cats in astronaut helmets. Their strokes fall in unison.

Crow Island is two acres of low pines and sea-scoured bedrock. Its improbable sovereign greets us at the landing: a lone rooster with museum-quality iridescence and the unimpressed air of a teenager newly aware that all rules have dissolved. He studies us with the patient appraisal of a local judging newcomers.

“What’s he doing here?” the kids ask.

“I have no idea,” my boss replies.

The kids pitch camp. The work of guy lines and rain flies is halting, earnest. Only D. operates independently; his one-person tent rises with unshowy competence. Em, Dr. S. (the English teacher), and I claim the girls’ corner of the site. D.’s tent is an adjacent outlier.

As dinner prep begins, two fishermen idle up in a skiff asking whether we’ve seen a rooster. Someone dropped it off “as a joke,” they say, not expecting it to last the night. The students exchange glances. “We haven’t seen anything like that,” they assure them, with diplomatic gravity.

Riccardo—christened shortly thereafter—has already melted into the underbrush. He resurfaces at dinnertime to slurp skeins of spaghetti that have escaped our pots and landed on the schist. The kids proclaim him a “leave-no-trace master.”

The next morning, Riccardo’s 4:30 reveille sends us paddling to Louds Island. Wind and tide push stubbornly against us. My boss tows two stragglers; I tow another. A sunken working boat sits half-submerged just offshore, an object lesson in maritime humility.

Lunch is behind a windbreak of rugosa roses. I ask Dr. S. what sixth-graders are reading these days.

Their list, she says, is “shockingly conservative—forty years out of date.” They’ve just finished Lord of the Flies, a novel she thinks “no longer maps onto their reality. It’s too grim, too anchored in Cold War pessimism.” Literature, she insists, should help kids imagine a better future—not just fear it.

The phoneless kids court boredom. They’ve “scrolled” the beach with their eyes and can’t take photos—what else is there? Then the old instincts reemerge. A rock-skipping contest materializes. Minutes later they discover the bilge pumps double as water guns, and the shoreline dissolves into a gleefully unregulated maritime skirmish.

By evening, they’ve settled into a functioning small society. Em rules the card table; D. retreats early to his tent. The others follow as a July drizzle begins, scattering the stragglers to their tents.

Then—just before midnight—footsteps. A bathroom mishap in the now-torrential rain. Tents unzip in a chorus. Teachers triage. Dr. S., unfazed, gives up her tent. D., wordless as ever, shifts aside to make room for the displaced tentmate.

By morning, everyone knows—and no one mocks. Hot chocolate circulates. Tents come down. Riccardo pecks at leftover oatmeal with the entitlement of a small autocrat. We bid him, and the island goodbye, and paddle toward the base in a straight, determined line.

The van absorbs all the gear, still without AC. Phones are handed back. But something in the kids has shifted; no one reaches for theirs right away. Em lingers last.

“Thank you,” she says. “I didn’t think I could do this. But it wasn’t bad. I actually loved it.”

Lord of the Flies endures on syllabi because it reassures adults that our darkest suspicions about children are correct: given enough time and weather, they’ll eat each other alive. It’s a strangely comforting myth. If kids are innately feral, then none of us are to blame for anything.

But Crow Island offered no such reading. The kids built something closer to a mildly dysfunctional start-up: inefficient, occasionally chaotic, but fundamentally cooperative. Their instincts were stubbornly practical—observe, adapt, carry on—more field-biologist than barbarian.

On the last evening, before the midnight bathroom catastrophe and its soggy reshufflings, I was scrubbing the cookware on the western rocks where the granite tilts toward the sea. Riccardo lurked nearby, riding the high of a day spent free-ranging and stealing calories. He watched each pot with the confidence of someone who has realized he cannot be fired. When it became clear I had no further offerings, he gave a theatrical shake of his feathers and strutted off, dignity intact.

Which is when the porpoises arrived.

Two of them—one small, one large—surfaced in neat tandem between a red nun and the dark spine of Hog Island. They moved with the kind of casual coordination group projects only dream of. I considered calling the kids. Then I imagined the stampede, the dropped headlamps, the inevitable questions about whether this “counted” as seeing dolphins.

I let the moment pass.

The kids would have loved them, of course. But it felt right to leave them something undiscovered—proof that the island still held a few surprises in reserve. A reason to return someday, when they’re older, or more patient, or simply bored enough to look up from whatever replaces phones by then.

Maine Guides

SUN BLANCHED THE Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife building in Augusta, just off the Kennebec River. I’d been in the state ten days but had mentally emigrated months earlier. All winter at 10,000 feet in Colorado, I’d been thinking at sea level. I checked in early—9 a.m., thirty minutes to spare. The state official looked me over, then at the swollen tote in my hand: snacks, a thermos of Earl Grey, borrowed charts, navigation tools rattling with borrowed confidence.

“You ready now?” she asked. “You were supposed to go second, but the first person canceled. You can head down if you like—just not with the thermos.”

I glanced at my new boss—mentor, witness—who’d come along for moral support. He nodded.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s go.”

We descended past a barred owl arrested mid-glare and a bronze Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby—Maine’s first Registered Guide—forever mid-cast. My novice seamanship earned no approval from her fixed attention. Downstairs, more glass-eyed birds kept watch over two very alive assessors. The official left to gather the other candidates; the door swung shut.

“We’ll start with navigation,” said the first assessor, gesturing to a laminated chart of Penobscot Bay. She handed me a sheet outlining the legs of an imaginary passage. Her eyes flicked to the parallel ruler trembling in my hand.

“You brought your own tools,” she noted. “All right, then. Your fifteen minutes start now.”

Registered Maine Guides are licensed to lead others through the state’s wild—over ledge and lichen, across water and ice. Popular mythology still pictures the archetype as a flannel-wrapped woodsman, a bearded figure lifted from an old L.L. Bean catalog. But the first person to hold the license, Maine Guide No. 1, was not a man. It was Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby, a forty-three-year-old bank clerk whose authority in the outdoors was neither inherited nor romanticized.

Born in 1854 and orphaned early by tuberculosis, Crosby was advised to “walk out the sickness.” She began doing so literally, following the Sandy River until she stepped past the perimeter of her life. She learned from local woodsmen and from Wabanaki knowledge keepers—people for whom these waterways were not recreational spaces but ancestral corridors. They taught her what moved, when, and why: trout behavior, seasonal winds, how a river reveals itself to those who watch long enough.

Crosby did not marry, had no children, and took up outdoor life relatively late. In 1886, a friend placed a bamboo rod in her hands—a five-ounce instrument of precision. The line sang. A storm on the river, she wrote, “set her on her course.” She returned to town with shoes full of silt and an unnamed shift in orientation. That night she wrote for the first time under the alias “Fly Rod”—plainspoken essays that treated the outdoors as a place of work, not bravado. She was skeptical of mystique. “I would rather fish any day than go to heaven,” she wrote. Not a metaphor. A preference.

By the time Maine formalized guide licensure in 1897, Crosby had spent a decade establishing that a woman in the woods was not an aberration. She earned License No. 1.

She sits in a broader, seldom-named lineage of women who became outdoor leaders not through institutional pathways but through repetition, observation, and necessity. Georgie White Clark, for example, didn’t run her first Grand Canyon trip until she was in her thirties, after losing her daughter in a car accident. Her explanation for becoming the first woman to row the full canyon was characteristically flat: “I didn’t mean to start anything. I just wanted to go down the river.” Mina Benson Hubbard—who completed the first accurate mapping of Labrador after her husband died attempting the same expedition—said simply: “I went because I had to go.” None framed their work as trailblazing. They framed it as common sense.

To become a guide is not mastery but resignation: this is the life that makes sense when nothing else does. The ones worth emulating rarely arrive early, or through straight lines. Crosby walked out her illness. Georgie White Clark rowed her way through grief. Mina Hubbard mapped Labrador because she could not allow the story to end with someone else’s failure. None of them framed guiding as a calling; it was simply the thing that remained when every other explanation fell away. That is the quiet commonality: not destiny, but inevitability. You follow the water, or the trail, or the chart, because you can’t imagine doing anything else. The work is orientation—first of yourself, then of the people who trust you to lead them.

After navigation came the rest of the oral exam: flora, fauna, boating regulations, first aid, and a mock emergency—a stroke on an island near Bar Harbor requiring a MAYDAY call. Ninety minutes later, I climbed upstairs for the written test. One hundred questions, pencil on paper. I turned it in and sat between Fly Rod and the owl, watching my boss pace outside. I looked at her bronze gaze, not his outline, and waited.

Soon the official called me forward. She opened a Tupperware of patches—embroidered ocean blue, iconic.

“How do you want to pay for your new license?” she asked.

28 hr (1,873.3 mi) via I-80 E

Mile 1

My life in a box

at seventy miles an hour—

winter home recedes.

Mile 74

Road signs like old friends,

markers of seasonal life—

one journey, two homes.

Mile 562

Flatness, everywhere.

Time itself has leveled out—

must be Nebraska.

Mile 1487

Another podcast.

“Ohio,” GPS laughs—

nine hours to go.

Mile 1776

Road steams with insects;

even headlights feel soggy—

“welcome back, East Coast.”

In The Land Before Time

THE AVALANCHE-SWEPT Chilkat Mountains rose above me, and the silver-grey saltwater of Lynn Canal stretched out below—a long exhale from summit to sea. I could feel the transition in my ribs as clearly as the dry bags clattering in the hatches of my loaner NDK Explorer.

It had taken two flights, a five-hour ferry, and months of saving and circling REI clearance racks to reach Haines, Alaska. First came the Southeast Alaska Sea Kayak Symposium; then a five-day expedition along the northernmost corridor of the Inside Passage. I understood immediately why it’s named that—inside. Protected waterways, yes, but also a corridor that pries open whatever you’ve managed to keep sealed. Miles through wilderness, and miles into your stowaway self.

In Southeast Alaska, rain doesn’t fall—it inhabits. It rises from the ground, settles into your bones, and claims you with quiet authority. Forty degrees here is not forty degrees in Colorado. I doubled baselayers, added a vest, swapped gloves. I accepted dampness as the price of admission into a domain ruled by whales and grizzlies.

On the morning of May 6, the journey stopped being weather forecasts intersecting lines on a chart. We left our luggage onshore and paddled off—just me, my seventy-six-year-old paddling partner, the Wolf, and our two unfussy, unflappable guides. The Wolf is compact and deliberate, the kind of paddler who wastes no motion. He rolls without drama, comes up blinking and expressionless, and settles back into a steady cadence that seems older than he is. Age shows mostly in the way he pauses before lifting his hull onto his truck. Once he’s in the boat, it’s gone. Sea kayaking suits him: a discipline where economy outperforms strength and longevity is earned stroke by stroke.

That first day was a reminder of what the body remembers when asked gently: the slip of the blade in cold water; the way engagement from the feet spares the shoulder later. Rain held as we moved past ululating scoters, sea lions rising like pylons from the dark, and pocket beaches arranged as if for a postcard. We pitched our tents on Shikoshi Island, devoured burritos, and collapsed by nine under a sky that never fully darkened.

While the guides scrubbed microscopic hints of food from pans down the beach—bear country etiquette—I climbed onto a rock, bear spray at my hip. Far enough to feel alone; close enough to still be found. The stillness was immense. Unexpectedly, a thought surfaced: I wish my mom could see this. The tears followed with no fanfare. Grief can feel dormant for years, then rise cold and quick as tidewater. The landscape was large enough to hold it; I let it.

The Chilkats are younger than the Rockies where I grew up and now winter. Lower, yes, but geologically restless—glaciers still softening their flanks, moraines drawing straight lines down to the sea. No roads, no lifts, just tectonics and time.

“That’s the Davidson Glacier,” the local guide said, pointing to a blue-brown cradle of ice high above. “In Muir’s time, it calved right into the water.”

As the sun slid behind peaks, a strange memory visited: an old VCR tape, an animated ridge line. The Land Before Time. I hadn’t thought of it in decades, but in that moment the echo was unmistakable—mother loss, the ache of separation, the long pursuit of a new valley. The film had carved something into me, a glacial striation I didn’t know I carried.

The next morning, a black triangle flitted at the surface. “Orcas,” our lead announced, already scanning. “Moving north. Do you see?” I did not. “There. Sometimes I swear people think I’m full of shit.”

Wind came up. Then died. Then returned. When my fingers throbbed with cold or when peeing through four layers felt like a complicated moral exercise, I whispered my private mantra: You chose this. You gave your time and money to be here.

But as the days wore on and the landscape wore me into it—like rivulets braiding down a mountainside—I wondered if I chose anything at all. Or if choice is only a polite name for current and countercurrent, a slack tide flipping direction without warning.

When the wind eased just enough for the guides to greenlight our crossing, I imagined every failure point: capsizing in the cold, soaking my tent and sleeping bag, blowing my angle and drifting toward the sea-lion rocks. You chose this, I repeated. But the water had its own ideas. We reached mainland, exhausted and relieved. The Wolf collapsed on the beach, still sealed into his PFD like a child who’d fallen asleep in a snowsuit.

We would need to make up at around twenty-five nautical miles the next day. While we ate tortellini, the lead looked out toward the channel and said, almost offhandedly, “I see sun on the horizon.” I took that into my tent like a borrowed talisman.

This summer I’ll guide not in Alaska but in Maine. Still, that trip handed me a horizon wide enough to hear the quiet part of myself say: This is why. Not because an inner adventurer needs indulging, but because something in me recognizes the utility of maps, bearings, crossings. Watching the guides hang tarps, call out bear-fence placements, decipher wind with a glance, I wondered which kind of guide I’ll become. Whether I’ll be good. Whether I’ll enjoy it.

When I was young, I wanted to be an “explorer.” The adults laughed, partly because I was a girl and it was the 90s, partly because modern life insists there’s nothing left to explore. But the explorers I loved—Frodo, Littlefoot—weren’t charting territory. They were leaving the familiar because home had changed shape beneath them.

The realization surfaced gently, like the mother humpback and calf we encountered on our third day. The mother exhaled first—tall, resonant. The calf followed, a smaller punctuation. They moved alongside us, unconcerned. A quorum of gulls marked the bait ball beneath. They knew we were there. They simply didn’t adjust themselves around our presence.

Maybe I am not seeking the thrill of new terrain but the permission to feel something primordial that has always been at the waterline—grief, wonder, memory—held long enough to come up for air.

The primordial is not ancient or remote; it’s as ordinary as dropping the skeg and turning downwind. In my boat, I am Littlefoot—small, unsure, moving through immensity anyway. Or like the fire our local guide attempted on our last night in Berner’s Bay—rain-soaked wood, no kindling, no chance. She kept at it. Then, the Wolf remembered the cracked cutting board in his hatch. We fed it to the flame. Finally, a spark held.

Many times the earth beneath me has shifted—divorce, death, breakups, pandemic. Sharp-tooths abound. But the “Great Valley” is not a destination; it’s a clearing, a pause, a space where grief exhales without demanding resolution.

Back in Juneau, our re-entry to time coincided with Mother’s Day. A holiday I’ve long treated like a bruise—best ignored. Brunches, flowers, the forced sentimentality of it all. But that day, moving through gift shops and trailheads dotted with mothers and daughters, I didn’t brace against anything. I just moved among them. I chose to be here, and found I could.

Maybe that’s what the Inside Passage teaches best. Not grandeur or grit, but access—to the remote places outside us, and the more remote ones within. Five days in the Alaskan backcountry loosened something that had been calcified in me for years. The grief didn’t vanish. It simply found room.

Southeast

JUNEAU

Rainforest welcome:

skunk cabbage brightens wet trails,

fog stitches the woods.

HIGHWAY

Fjord currents ferry

skiers northbound for Skagway;

I will paddle back.

SYMPOSIUM

Truck with boats pulls in—

Hera finds me on the pier,

paws parting the rain.

HAINES

Hammer museum,

people exist between scars

of avalanches.

XTRATUFS

Brown boots everywhere—