28 hr (1,874 mi) via I-80 W

Ohio

Ski bro at the pump—

Jersey plates, puffy jacket,

knowing nod ensues.

Presidential

Birthplace of Lincoln—

green signs lecture as we drive.

Birthplace of Reagan.

Work Zones

Chevrons flash orange.

Arteries of asphalt squeeze;

neon hazards glow.

Iowa

Turbines rake grey sky.

Billboards preach roadside gospel—

America shrugs.

Accident

Semi on its side,

tipped like a child’s toy truck—

steel guts glint in sun.

Ovid, CO

Metamorphosis:

state lines shift, the earth stays flat—

Nebraska, but not.

MOI

My knees were cold from kneeling in wet November leaves. Someone was playing an unconscious victim with unnerving conviction, half buried in duff. I palpated her limbs the way you check a jacket pocket you’re almost certain you haven’t lost your keys in—half hopeful, half afraid of what you’ll find.

“Just remember,” our instructor called out, hands tucked into his vest pockets, tone dry as tinder, “CPR doesn’t work in the woods. Hurry up and figure out what’s wrong with your patient.”

He wandered over to inspect my technique, which at that moment consisted mostly of wrestling my patient onto a sleeping pad and rooting, somewhat desperately, for a carotid pulse.

“Don’t reach over your patient like that,” he said. “Take the pulse on your side. Otherwise you’ll strangle her.”

Killing my first patient felt like a reasonable beginning to Wilderness First Responder—known, with varying degrees of affection, as “Woofer.”

For ten days, our group of twenty-one strangers revived plastic infants with stiff limbs, treated imaginary drunk campers, and staged the mass-casualty aftermath of a downed gondola in the pines of New Hampshire. Mornings meant rolling out of bunk beds, submitting gratefully to Nancy’s enormous breakfasts—Nancy being the campus cook and, by consensus, the only person keeping the entire operation emotionally solvent—and marching into the cold for scenarios. We memorized the necessary acronyms: AVPU, ABCs, SOAP. But the one that rooted itself most insistently—lodged, really, the way an impaled branch might—was MOI.

Mechanism of injury.

The origin story of pain.

The plot twist that gets you here, cosplaying catastrophe in the woods.

Outdoor professions attract a familiar cohort: the recent graduate not quite ready for a desk, and the retiree who spent twenty years at one and finally suffered the sort of existential rupture that results in a backpack purchase. Because of finances, there is very little in the middle. The twenty-two-year-olds are perfectly content to live under tarps in a state of communal, provisional bliss. The retirees, meanwhile, can afford to resurrect the happiest memories of their youth with the zeal of someone performing chest compressions on nostalgia. The metronome remains the same, but the song used to keep rhythm has shifted—from the Bee Gees to Chappell Roan—leaving those of us with aging but still functional knees and long Zillow wishlists in a kind of generational no-man’s-land.

Around me sat human clippings from a vintage REI catalog: rookie ski patrollers; a seventy-year-old scientist who surveyed remote Alaska; a retired teacher moonlighting with search-and-rescue; a twenty-something backcountry ski guide; a young “brown bear” guide fresh off his summer in the Kenai Peninsula; an eighteen-year-old New Yorker whose motives remained inscrutable; a nature therapist in her sixties. Only two people were in my age bracket. We spotted one another immediately, exchanging the quiet recognition of travelers who’ve missed the last ferry and now occupy the same dimly lit dock.

23 YOF.

70 YOM.

40 YOF.

Even stripped to the barest patient identifiers, we were an earnest, slightly improbable cast—twenty-one strangers who had, in various ways, accepted that the wilderness is where one eventually meets the hard limits of the human body.

“What’s our favorite word?” the instructor asked one morning, tapping the smart board with a digital pen that seemed to please him disproportionately.

“Continuum!” the class replied, as though it were a moral directive.

And in a way, it was. Everything, we learned, exists on a continuum: shock, infection, heat injury, hypothermia, traumatic brain injury—which the instructor colorfully described as “the brain trying to leave the skull through the big hole.” Careers, relationships, and taxes share the same sliding-scale inevitability. Talking nicely and sugar water, we were assured, help with most things.

“At the end of the day,” our instructor announced, “we’re all fucking hummingbirds.”

By then we had practiced impalements, strokes, heart attacks, broken ribs, tourniquets, and death notifications. We stabbed training EpiPens into our thighs and splinted one another’s intact bones with sticks and sleeping pads. Underneath the theatrics pulsed a quieter question: Will I ever need this? And: Will that ever be me?

Last year, it was. I had been a real patient. There is no moulage for c-word things. Nothing in the textbook—despite its generous enthusiasm for diagrams—prepares you for the way a medical event can rearrange your sense of chronology. My MOI was internal, discreet, the sort of plot point you can’t point to on a map.

Pema Chödrön writes that “nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to know.” If that isn’t a continuum, I don’t know what is.

By week’s end, EMT Sensei—his own MOI wrapped neatly in a knee brace—led us to a ridge where five classmates and two mannequins lay strewn in dramatic disarray, moulaged with almost theatrical verve. Moving toward emergency always feels like approaching a mirror: the mountains we climb, the waters we cross, the people we love; the moments when things go wrong and you kneel beside a body, hoping your hands remember their choreography.

“So, what did we learn this week?” he asked on the final day.

“CPR doesn’t work in the woods!” we shouted.

But the unspoken second half had become obvious: But that doesn’t mean we don’t try.

I tucked my badge away and climbed back into the Subaru, pointing myself west. At my cushy resort mountain, is ski patrol. Helicopters on call. An army of elite orthopedic surgeons.

But first responder training isn’t about conquering chaos or even saving lives; it’s about cultivating a kind of interior ballast. The ability to arrive—at accidents, at relationships, at your own life—with a little more steadiness than the day before. To assess scene safety first, then decide whether you have a duty to act. And if you don’t, whether you will act anyway. It’s about widening, however minimally, the fragile circle in which you may be able to make something a little better. Including, it turns out, the slow, awkward business of getting older—especially when you find yourself wedged between the sendy, twenty-year-old hopefuls and the sixty-something wilderness sages. It is, like everything else, a continuum.

In the end, MOI feels less like a mechanism of injury than a mechanism of insight: why we are drawn to these places, why we return, why some of us build our odd little lives at the edge of weather and chance.

And why, in a hexagonal building in New Hampshire, twenty-one strangers worked so intently—earnestly, imperfectly—to learn the simplest and hardest thing: how to keep one another alive.

First Frost

Hoar

Yard sighs, mother-gray;

brittle blades wake silver-spined—

the forest shudders.

Mr. B. B. Says

“Used to be August,”

he sighs of October rime—

“frost’s gone by lunch now.”

Layers

Fog, river’s cashmere;

Hudson layers for the cold—

winter waves hello.

Dry Suit Season

Neoprene to wool—

paddle will soon be ski pole;

make sure zippers close.

Rekindling

Screen door still open;

J lights the woodstove and waits—

embers find their breath.

Denning

Bears nose through the duff;

out back, a tarp snaps in wind—

snow hums in the pines.

On HABs

Spring and fall are bookmarks of brief homecoming. My little farmhouse liberated from Airbnber’s waits for me, tucked in between the toes of New York’s storied hills. More base than home at this point, the sturdy structure built by the hands of neighbors who still dwell on either side of me, up and down the valley, serves for much of the year as gear storage, waypoint, repository of pasts and perhaps-future lives. But in May, a little of June, some of September into November, once again, it’s home.

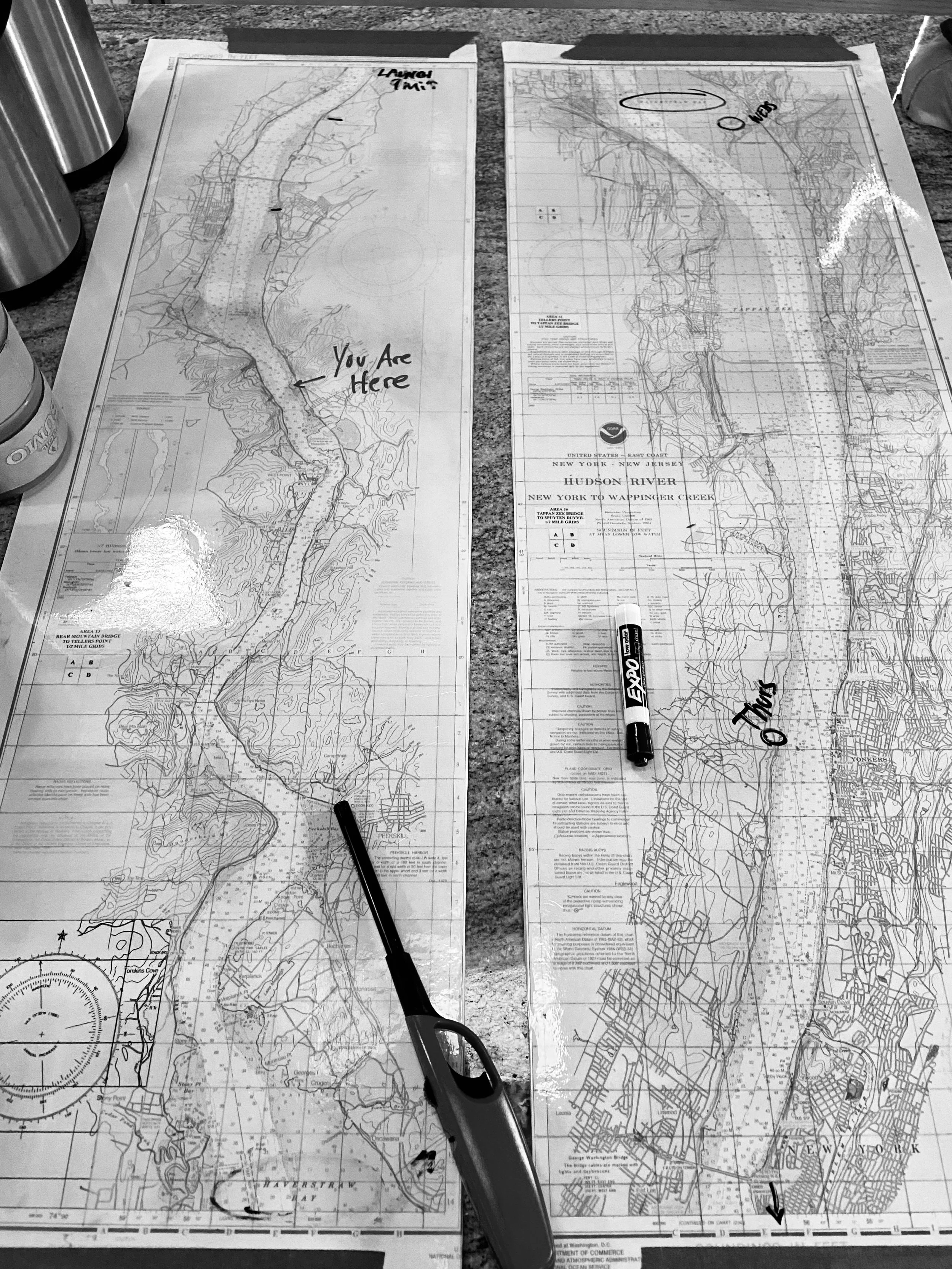

The whole way down I-95 from Maine, my salt-streaked Delphin snake-strapped to the Subaru’s roof, I’m eager for it. Not just the house with its king size bed with a deliciously firm mattress, but also my so-called homewaters. The Hudson riparian zone flows the warm, familiar brackish where I first slalomed bow-draws through waterlilies that raft in the back-eddies. But before I can even unload the car, a warning from local paddlers lands in my inbox: HABs—harmful algal blooms—on the Hudson.

Kingston Point Beach, my closest and most familiar little launch, is closed.

If the decades of my life are book chapters bound by a crooked a spine, it is the Hudson. Before I was a paddler, the river bookmarked a layer I barely even perceived—an urban wind tunnel in winter, a summer fringe to the High Line, a moat separating “the center of the world” from its antithesis, New Jersey. Then Covid redrew the isobars of my life. I crossed the GW Bridge, followed the estuarine gradient upstream, and settled in the headwater hills the river once carved with ice.

Then, three summers ago, the Hudson became my kayak nursery and classroom: first strokes and wet exits, rescues practiced in green-brown chop, the path that led to my instructor cert with Hudson River Expeditions. My first overnight as a sea kayaker—a seventy-mile, four-day descent from Poughkeepsie to New York—felt like traveling a trophic and cultural cline, the ebb pulling us beneath iconic bridges like beads: Mid-Hudson, Newburgh-Beacon, Bear Mountain, the re-christened Mario Cuomo, and at last the little red lighthouse tucked under the GW. To paddle my way back into midtown was to tie off a transition between life eras with a tidy bowline: from city-bound writer to outdoor professional, strung along a single body of water.

“The Hudson was once a cesspool of filth,” the history-buff kayakers love to remind you. “For centuries, people dumped all kinds of crap here—dioxins, pesticides, raw sewage. Indian Point left its mark, and GE, worst of all, poisoned whole reaches with PCBs. The cleanup only began in the 1970s. Amazing we can even paddle here now.”

The worst outbreak of blooms in 40 years inscribe the present tense in a scientist’s lexicon. Cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton—neither fish nor tree—are photosynthesizers catalogued by color and clade: green, red, brown; diatoms, dinoflagellates, blue-greens. In balance, they underwrite primary productivity, turning light into living carbon. But increase nutrient loading—sewage, lawn runoff, manure; warm the water; slow the flushing—and eutrophication takes hold. Pigments slick the surface like spilled paint. Some blooms merely shade; some produce toxins. All are a message in dissolved oxygen and turbidity: choke the light, starve the gills, tilt the river toward hypoxia. Longer heat stretches stratification; drought reduces turnover; nutrients light the fuse.

It’s not just the Hudson, either. In Maine, they warn of “red tide.” After heavy rainfall, shellfish become suspect. While clams and mussels can purge in days or weeks, oysters bioaccumulate and hold toxins like childhood memories.

Our first weekend back, we drive to Cornwall to meet my paddling buddy, the Wolf. He’s had a birthday since I last saw him at the Seattle airport sitting at a Chinese restaurant in the terminal not quite thawed from our expedition. Seventy-seven Augusts and counting, he now boasts a gold hoop in his left ear and a turkey feather tucked in his hatband. “Talismans,” he calls ‘em, to sanctify his new status as a kayak guide.

Before he ever got the gig, he guided me. We met unloading the same boat, Alchemy Daggers, at Kingston Point, and have paddled together ever since. From Rhode Island to Alaska, the Wolf’s hand-of-godded and towed me out of trouble more times than I care to admit.

This summer, he’s been leading trips Bannerman Castle, the eccentric ruin on Pollepel Island. The HAB index down here isn’t high enough to cancel tours, so he launches our group in the shallows and waves us off the barge wake. Little green dots whirl off my paddle like confetti. A spotted lanternfly touches down on my hat brim—cryptic gray forewings, sudden aposematic red beneath.

“Kill it,” the Wolf says, soft but absolute. “Slowly, if you can, to send a message to the others. They’re very invasive.”

Maine’s erratic lobstermen and postcard beaches give way to New York’s working waterway. Here, paddlers thread wake, wind, and weekend barges. City etiquette seeps upstream—sidewalk habits translated to current and channel. The boats dodge, shift, merge. The tour crowd changes, too—New Yorkers, kin to New Englanders, but tempered: grittier, somehow sleeker. A Women’s History professor from Albany tells me why she drove her family three hours downriver to kayak today: “History,” she says. “What else?”

We cross on slackening flood and scramble over the rocky landing, slick with periphyton. The Hudson doesn’t swing ten feet like Maine waters, but its three-foot tide still breathes diurnally through this fjorded valley. A volunteer guide in a BANNERMAN’S CASTLE shirt with a Long Island lilt gathers us by Mrs. Bannerman’s pie garden. The Wolf hangs back, chewing the inside of his cheek. He knows the script; the island’s story is an American geomorphology of ambition and decay.

“In 1900,” the guide begins, “a Scottish immigrant named Francis Bannerman VI purchased this rock and began building what he called his Arsenal…”

“He was the country’s original arms dealer,” the Wolf whispers, jumping ahead of the official narrative. “Ran the biggest military surplus operation that became the Army Navy Surplus Store. This place is an adult game of hide-and-seek.”

The guide confirms the Wolf’s footnote: after the Spanish–American War, Bannerman bought 90% of the US military’s unused weapons, uniforms, and black powder—so much that Brooklyn officials blanched at the thought of his munitions next door to the naval yard. The baron desired storage and spectacle, so he doodled himself a castle—part Scottish baronial, part billboard—its crenellations spelling BANNERMAN’S ISLAND ARSENAL for every passing steamboat to read. Poured quick and cheap, the concrete fairy-tale went up quick. For a time, it advertised a fast-tracked empire.

Then came the classic Gilded Age parabola: the warehouse exploded in 1920, Bannerman followed soon after, and the slow unspooling began. In 1969, fire set the period at the end of the sentence. What’s left is a buttressed rib cage open to weather, a shell that now stages local theater and a ruin Metro-North commuters know by heart—a concrete pastiche of The Great Gatsby’s closing line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Last year, when my surgery kept us in the Catskills longer than planned, J. became one of those commuters. Three times a week he watched the ruin drift past his train window and wondered, What is that place? Now, circling the bones of its drawbridge by kayak, he carries the gleam of a boy in his first European dungeon. Pattern recognition fires.

“It’s like the AI bros of today,” he muses, and the history professor chuckles. “All in on a good idea, no training or foresight. Hoard the tech, ignore the regs that are coming, pretend obsolescence won’t arrive. I call it the ‘let’s-build-a-fort’ mentality. That’s what this Bannerman dude did—and look what happened.”

“Spot on,” she replies. “Everything that’s happening now is not unprecedented. Only question is: what’s your role in all this going to be?”

The Wolf’s role is clear.

“Four o’clock!” he cries. “Time to go!”

His bow edges out, turkey feather an exclamation point. The historian tracks his line across the channel toward the take-out, reading the microcurrents by the feather. Green freckles wink in our wakes. She flicks a lanternfly from her shoulder; it pinwheels on the miso-colored surface. J.’s comparison lingers. If Bannerman’s boom is a parable for our extractive cycles, the HABs are nature’s bots: cellular networks that, in low abundance, the system metabolizes—but with heat, stagnation, and feed, they scale into systemic risk. Lethal for pets and harmful to humans.

Contamination isn’t dramatic; it’s steady—like sedimentation, a floodplain filling grain by grain. To get rid of the HABs, as the Columbia Riverkeeper says, the task is none other than tackling climate change itself: “…we need to reduce nutrient inputs from industrial chemicals, fertilizers, manure, and human waste; increase water flow; address the temperature impacts of dams; and curb climate change.”

While small efforts from individuals can always help, like picking up pet waste, the true remedy is for it all just to stop. Then wait for as long as it takes for the water to clean itself. But once the bloom is here, there’s little that can be done. Don’t swim in the waters, keep the dog away, and, in time, maybe it’ll dissipate.

“For time is the essential ingredient,” writes Rachel Carson in Silent Spring; “but in the modern world there is no time.”

The next day, J. and I head to the Hudson Valley Garlic Festival. Eighty degrees in late September. Saugerties is a mosaic of garlic hats, witches, vampires, and soil-rich hands. In the hay-bale commons, the Arm-of-the-Sea Theater unfurls a puppet river in cerulean silks and sings a song about photosynthesis to a chorus of equally delighted adults and kids. The troupe’s mission—“handmade theater as an antidote to ubiquitous electronic media and consumer culture”—ripples through the crowd as boos meet the colonial realtor and cheers rise for hemlock, oak, and pine. Some of us are locals; some are not. Everyone is listening. For the finale, the bear waddles onstage with a kayak cinched around his belly, paddle in paw. He dips the blades into imagined current, singing of environmental resilience to papier-mâché trout and city transplants alike.

Tucked in the generous allium bounty of small farms, the play reminds me the Hudson holds more than ruin and warning. Time may be short; creativity is not. New York hope is granular—plankton-small, stitch by stitch—gathering in community theater, in a professor’s silent paddle cadence, in the turkey feather on a 77-year-old guide’s hat.

As sea kayak guides, we lead people into many waters. In Maine we sell clarity—porpoises and ledge ecology, tidal respiration you can feel in your bones. We point to eiders surfing swell, pull out lobster gauges, and say, look how well the world keeps working. It’s easy to forget that Rachel Carson spent her summers on Southport Island, just across the bridge from Boothbay Harbor where I lived this summer—and that her time there shaped the work that helped end DDT’s reign. Without her, the islands where I taught kids to Leave No Trace and delight in shorebird abundance might have read differently. As the history professor reminded us: none of this is unprecedented. The bots aren’t new tech. They’re just the same old contaminants in a new form. Throughout human history, they’ve appeared, accrued, attacked—but they’ve also been diluted, diffused, and defeated.

The Hudson’s lesson isn’t so different. The Wolf threads us through the arteries of an overbuilt watershed to a Gilded-Age folly between interstate bridges. The riparian speaks in closures and neon veils, but also in the older key of resilience and succession: flood-pulse, leaf-drop, Forever Wild. On the banks, a countercurrent slowly gathers—garlic-festival crowds, hay-bale audiences, a bear in a cardboard kayak. Creativity is the Hudson Valley’s unique civic hydrology: it braids strangers, slows the current of despair, and makes room for oxygen.

The river remembers how to heal. We must remember how to belong.

28 hr (1,873.3 mi) via I-80 E

Mile 1

My life in a box

at seventy miles an hour—

winter home recedes.

Mile 74

Road signs like old friends,

markers of seasonal life—

one journey, two homes.

Mile 562

Flatness, everywhere.

Time itself has leveled out—

must be Nebraska.

Mile 1487

Another podcast.

“Ohio,” GPS laughs—

nine hours to go.

Mile 1776

Road steams with insects;

even headlights feel soggy—

“welcome back, East Coast.”

Southeast

JUNEAU

Rainforest welcome:

skunk cabbage brightens wet trails,

fog stitches the woods.

HIGHWAY

Fjord currents ferry

skiers northbound for Skagway;

I will paddle back.

SYMPOSIUM

Truck with boats pulls in—

Hera finds me on the pier,

paws parting the rain.

HAINES

Hammer museum,

people exist between scars

of avalanches.

XTRATUFS

Brown boots everywhere—

locals wear them like logic,

the tall ones only.

RESCUES

Cold bites the dry suit;

T-rescues in the warm pool—

small rehearsed mercies.

BOTH

Skin north, stroke back south—

skiing, paddling, all year long;

here, there is no or.

THE MAUL

Bear spray at my hip—

a constant, like a cell phone

with no reception.

DISTILLERY

Whisky tastes of sea;

Alaskans drink like weather—

deep, sudden, stormy.

BILLIKEN

Walrus-tusk carving—

a PFD talisman laughs:

“things as they should be.”

Mud Season

CLOSING DAY

Tourists clear out fast.

Now the mountains hum with mud—

just the way we like.

CHEAP DINNER

Snow tires still on.

Main Street maître d calls out:

“Half off for locals!”

SCENE CHANGE

Rivers rise and run—

an idea caught in between.

The thaw rushes on.