MOI

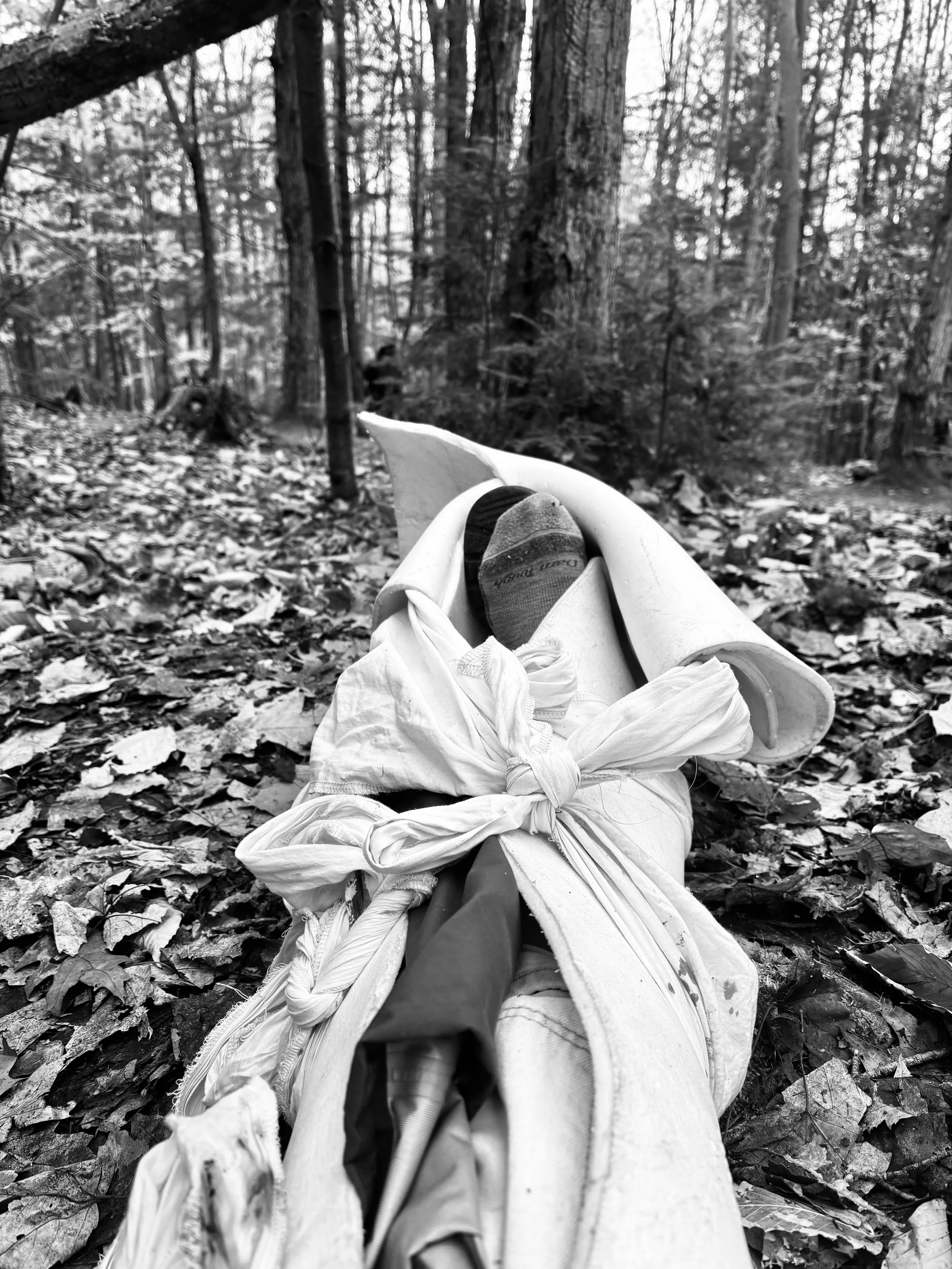

My knees were cold from kneeling in wet November leaves. Someone was playing an unconscious victim with unnerving conviction, half buried in duff. I palpated her limbs the way you check a jacket pocket you’re almost certain you haven’t lost your keys in—half hopeful, half afraid of what you’ll find.

“Just remember,” our instructor called out, hands tucked into his vest pockets, tone dry as tinder, “CPR doesn’t work in the woods. Hurry up and figure out what’s wrong with your patient.”

He wandered over to inspect my technique, which at that moment consisted mostly of wrestling my patient onto a sleeping pad and rooting, somewhat desperately, for a carotid pulse.

“Don’t reach over your patient like that,” he said. “Take the pulse on your side. Otherwise you’ll strangle her.”

Killing my first patient felt like a reasonable beginning to Wilderness First Responder—known, with varying degrees of affection, as “Woofer.”

For ten days, our group of twenty-one strangers revived plastic infants with stiff limbs, treated imaginary drunk campers, and staged the mass-casualty aftermath of a downed gondola in the pines of New Hampshire. Mornings meant rolling out of bunk beds, submitting gratefully to Nancy’s enormous breakfasts—Nancy being the campus cook and, by consensus, the only person keeping the entire operation emotionally solvent—and marching into the cold for scenarios. We memorized the necessary acronyms: AVPU, ABCs, SOAP. But the one that rooted itself most insistently—lodged, really, the way an impaled branch might—was MOI.

Mechanism of injury.

The origin story of pain.

The plot twist that gets you here, cosplaying catastrophe in the woods.

Outdoor professions attract a familiar cohort: the recent graduate not quite ready for a desk, and the retiree who spent twenty years at one and finally suffered the sort of existential rupture that results in a backpack purchase. Because of finances, there is very little in the middle. The twenty-two-year-olds are perfectly content to live under tarps in a state of communal, provisional bliss. The retirees, meanwhile, can afford to resurrect the happiest memories of their youth with the zeal of someone performing chest compressions on nostalgia. The metronome remains the same, but the song used to keep rhythm has shifted—from the Bee Gees to Chappell Roan—leaving those of us with aging but still functional knees and long Zillow wishlists in a kind of generational no-man’s-land.

Around me sat human clippings from a vintage REI catalog: rookie ski patrollers; a seventy-year-old scientist who surveyed remote Alaska; a retired teacher moonlighting with search-and-rescue; a twenty-something backcountry ski guide; a young “brown bear” guide fresh off his summer in the Kenai Peninsula; an eighteen-year-old New Yorker whose motives remained inscrutable; a nature therapist in her sixties. Only two people were in my age bracket. We spotted one another immediately, exchanging the quiet recognition of travelers who’ve missed the last ferry and now occupy the same dimly lit dock.

23 YOF.

70 YOM.

40 YOF.

Even stripped to the barest patient identifiers, we were an earnest, slightly improbable cast—twenty-one strangers who had, in various ways, accepted that the wilderness is where one eventually meets the hard limits of the human body.

“What’s our favorite word?” the instructor asked one morning, tapping the smart board with a digital pen that seemed to please him disproportionately.

“Continuum!” the class replied, as though it were a moral directive.

And in a way, it was. Everything, we learned, exists on a continuum: shock, infection, heat injury, hypothermia, traumatic brain injury—which the instructor colorfully described as “the brain trying to leave the skull through the big hole.” Careers, relationships, and taxes share the same sliding-scale inevitability. Talking nicely and sugar water, we were assured, help with most things.

“At the end of the day,” our instructor announced, “we’re all fucking hummingbirds.”

By then we had practiced impalements, strokes, heart attacks, broken ribs, tourniquets, and death notifications. We stabbed training EpiPens into our thighs and splinted one another’s intact bones with sticks and sleeping pads. Underneath the theatrics pulsed a quieter question: Will I ever need this? And: Will that ever be me?

Last year, it was. I had been a real patient. There is no moulage for c-word things. Nothing in the textbook—despite its generous enthusiasm for diagrams—prepares you for the way a medical event can rearrange your sense of chronology. My MOI was internal, discreet, the sort of plot point you can’t point to on a map.

Pema Chödrön writes that “nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to know.” If that isn’t a continuum, I don’t know what is.

By week’s end, EMT Sensei—his own MOI wrapped neatly in a knee brace—led us to a ridge where five classmates and two mannequins lay strewn in dramatic disarray, moulaged with almost theatrical verve. Moving toward emergency always feels like approaching a mirror: the mountains we climb, the waters we cross, the people we love; the moments when things go wrong and you kneel beside a body, hoping your hands remember their choreography.

“So, what did we learn this week?” he asked on the final day.

“CPR doesn’t work in the woods!” we shouted.

But the unspoken second half had become obvious: But that doesn’t mean we don’t try.

I tucked my badge away and climbed back into the Subaru, pointing myself west. At my cushy resort mountain, is ski patrol. Helicopters on call. An army of elite orthopedic surgeons.

But first responder training isn’t about conquering chaos or even saving lives; it’s about cultivating a kind of interior ballast. The ability to arrive—at accidents, at relationships, at your own life—with a little more steadiness than the day before. To assess scene safety first, then decide whether you have a duty to act. And if you don’t, whether you will act anyway. It’s about widening, however minimally, the fragile circle in which you may be able to make something a little better. Including, it turns out, the slow, awkward business of getting older—especially when you find yourself wedged between the sendy, twenty-year-old hopefuls and the sixty-something wilderness sages. It is, like everything else, a continuum.

In the end, MOI feels less like a mechanism of injury than a mechanism of insight: why we are drawn to these places, why we return, why some of us build our odd little lives at the edge of weather and chance.

And why, in a hexagonal building in New Hampshire, twenty-one strangers worked so intently—earnestly, imperfectly—to learn the simplest and hardest thing: how to keep one another alive.