Wet Exiting

It’s freezing out, the air sharp as broken glass, but I wedge my bulbous hot-pink kayak—Gnarvana, a name both ridiculous and true—into the back of my Subaru. I could have hoisted her onto the roof rack, but I don’t. The Silverthorne Rec Center is only minutes away, and there’s something comforting about the boat riding beside me, like a companion—belly down, waiting.

At the back entrance to the pool, the asphalt is frozen and slick, littered with the flotsam of other boats, paddles, neoprene skirts. Steam coils from the surface inside, rising to meet the cold like breath in winter. In this self-contained microclimate, another season—kayak season—clangs and splashes with life.

It’s the first pool session I’ve ever attended, despite two summers of whitewater paddling. I’ve come to wake up the muscles and coax out my roll. A teenage lifeguard scowls as I shoulder my creekboat through the double doors. My plastic hull knocks the frame. I rest her gently on the tile and wait for the hose.

That’s when I notice: mine is the biggest boat here. My Gnar is the only creekboat in a room full of sleek little playboats—Rockstars, Jeds, tiny, twitchy things designed to spin and spring. They lie in bright clusters at the shallow end, all angles and attitude.

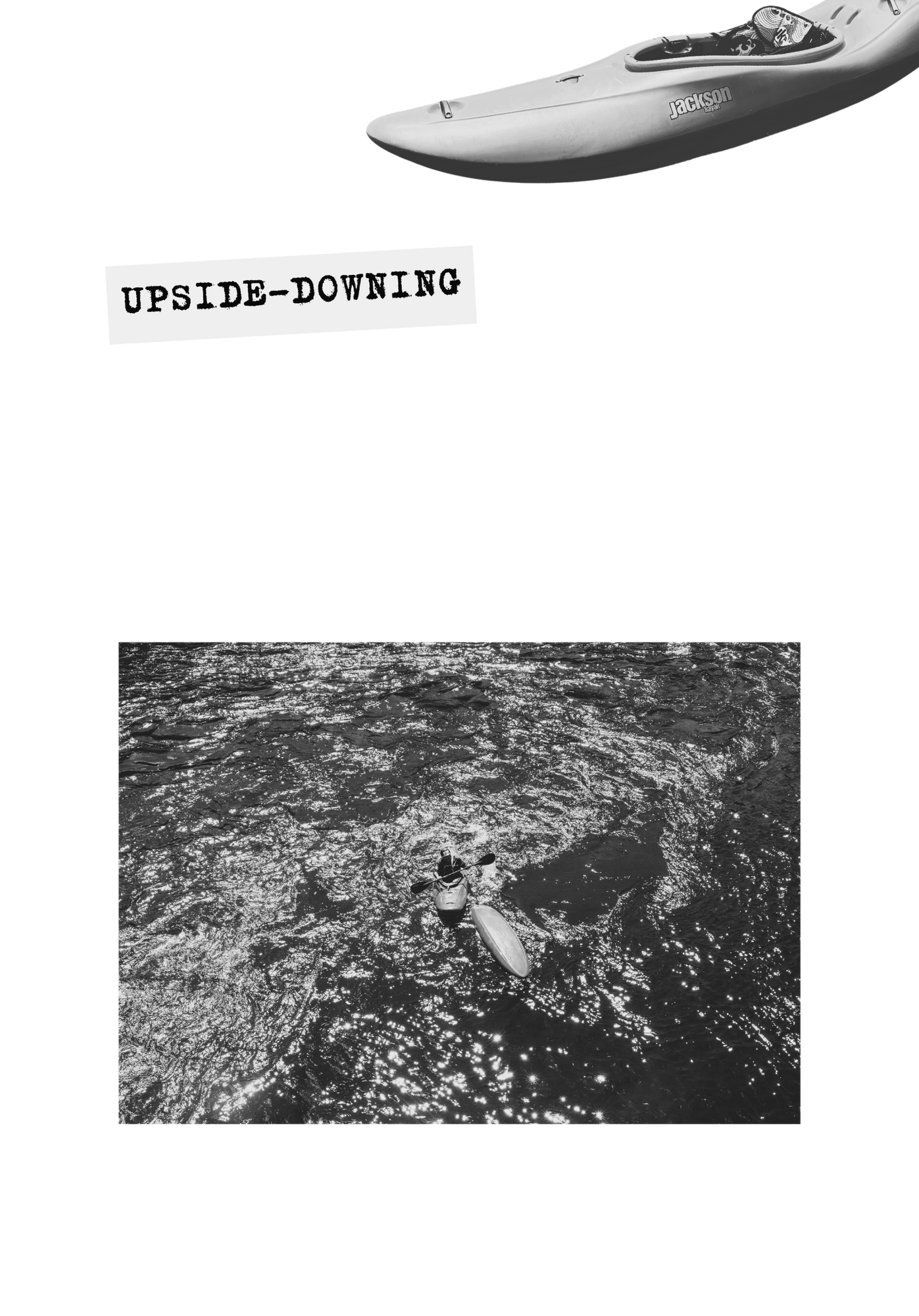

I pull my skirt on. The neoprene’s been hanging in the garage since November and resists, stiff at the edges. I fumble. Then I remember: lean back, pull forward, seal it tight. And just like that, I’m back in my boat. The foam hip pads embrace me. Were they always this snug? I nudge my bow under the water polo net and move slowly—feeling the weight of the paddle, the catch and pull of the blade through chlorine. Two guys in Rockstars are already upside down and right-side up again, breaching and spinning like orcas in fast, effortless cartwheels. They are confidently weightless. Laughter flows between them and the water—seamless, easy.

I paddle to the far end and begin again with the basics: the hip snap. I brace on the pool wall, bring my temple to the tile, and rock the boat side to side. For fifteen minutes, my head stays dry. But I didn’t come here to stay dry.

I capsize.

Set up for the roll.

And fail.

My ear breaches the surface too early, teases the air, then sinks again as the boat rolls me under. The old claustrophobia returns, slow and familiar: the tug of the skirt, the pressure of the cockpit, the panic blooming like ink in clear water. My hands reach, instinctively, for the grab loop. I pull. The skirt pops easily, like it expected this. A second later, I’m standing waist-deep in the water, kayak flooded, face hot—not from exertion, but shame.

No one else seems to notice. Or care.

But I do.

The wet exit is the first skill kayakers learn. Tuck. Tug. Tumble. It’s your safety net, your contingency plan. Swimming is not synonymous with failure. It’s what you have to do to survive when the world turns upside down and, for whatever reason, you can’t right it again.

The first time I wet-exited was more than twenty years ago, in a murky pond behind my high school gymnasium. The water was low that time of year, browned at the edges, the cracked shoreline still holding the last of summer’s drought. Our school had a canoe and kayak team, coached by Mr. L., who also taught tenth-grade English and walked the halls with a thermos of coffee and the smell of river on his boots. For our junior trip, we were to paddle a southern stretch of the Colorado River for a week. But first, initiation: we were to learn how to capsize and come up breathing.

It was a hot afternoon in early September. The bell had barely rung when Mr. L. ushered us through the chain-link fence to the back field. There, on the grass, lay life jackets, spray skirts, and a couple of sun-worn boats. He waved his arms like a conductor while his paddling team set about sorting the rest of us into small groups. I had rafted plenty—leapt laughing from rubber tubes into churning water, swum rapids with a guide’s shout in my ears. I was not afraid. When my turn came, I slid into the cockpit, no paddle, no worry, bobbing gently on the green water. Easy, I thought. What now?

I didn’t know it was coming. My partner, a boy I never spoke to with a bowl cut and a Metallica tee, was meant to prepare me. Instead, one moment he was explaining how to “kiss the bow,” and the next, the sky flipped. I was under—pondwater rushing up my nose, thick with the vegetal funk of duckweed and last year’s leaves. I panicked, flailed, and somehow loosened the skirt. I broke the surface coughing.

“What the hell was that?” I gasped.

“That’s kayaking,” he said, still laughing. “You did it! See? It’s our natural instinct to breathe!”

But it hadn’t felt natural. It had felt like betrayal—of air, of trust, of the body’s need to know what’s coming next.

When we chose trip boats, I chose the canoe. Open. Skirtless. A craft that left room for breath. I would paddle tandem with my best friend. We planned excitedly to rig our boat with ramen and a Discman yolked to speakers sealed into Ziplock bags. As talk turned to CD selection, all memory of the pond sank behind us like a stone dropped into the current.

We launched on the morning of September 11, 2001. At the put-in, word came in fragments: a plane had hit a building in New York City. Or two. A joke, maybe, or a freak accident. And then we were gone—no signal, no parents, only the huddle of canyon walls.

For a week, the river carried us through a fragile not-knowing. Redrock walls radiated their slow heat. Cliff swallows stitched the air beneath overhangs; canyon wrens sang from the narrowest slots. Below our boats, bass and brown trout drifted just out of sight. We built small fires that crackled into the dark and gathered around them, whispering hopefully of our lives after graduation. We slept under the wide bowl of sky, where no planes moved for five days, but stars came on like flint sparks. We were still children—buoyed by the belief that we were just beginning. That the world was waiting for us.

At the take-out, the illusion cracked. We stopped at a Wendy’s on the drive home. Inside, a television flickered in the corner, and newspapers lay abandoned in the sticky booths, their headlines shouting. Smoke coiled from Manhattan’s skyline. While we’d been floating, the world we were told we’d soon be grown enough to inherit had gone under. It never came back up.

So many years later, tiptoeing around the edge of a public pool—dripping, breathless, unsure—I realize it wasn’t just the memory of that first wet exit that returned. It was the memory of that pond leading to the river, more than twenty years ago. That current that carried us through one last week of collective adolescence—untouched, unsupervised, unbroken—has lived on ever since as a liquid boundary between naïveté and what came after. Not just for me and my friends as we stepped toward adulthood, but for the country itself.

In the American vernacular of the 21st century, there is a before and an after, a pre- and a post-9/11. That week floats in my memory like a drybag sealed tight. Nothing has leaked. Not the joy. Not the fear. Not the sense of having stood together on the threshold of what in retrospect is actually history, uncoiling into airports, classrooms, futures. Before we knew its name.

Last summer, I heard from a paddler I met on the river that Mr. L.—who had spent the last two decades teaching and coaching kids how to wet exit and cross eddylines—had passed away. Cancer.

“I just graduated last year,” my fellow alum said. “I can’t believe he’s gone. He taught me so much. And not just about paddling…”

Coming back to kayaking in my thirties isn’t about closing some old storyline or tying up loose ends. It’s not about mastery. And it’s not even about the memory of Mr. L., though he surfaces often. It’s about reconnection. About reaching for that fifteen-year-old girl who pulled the skirt and gasped—and offering her another chance. Not to get it right, but to learn how to right herself.

I didn’t nail the roll that first pool session. But I stayed after exiting. I called over my partner. He supported my boat while I moved through the motions—again and again. I put on my goggles and nose plugs. I stopped measuring myself against the playboaters with their tight spins and clean flips. I let myself stay underwater a little longer. I softened. I waited.

The roll is still a mystery. Some days it arrives like a bird landing on your shoulder—light, sure, unexpected. Other days, it’s gone without explanation. But that’s how it goes. It comes. It leaves. It returns.

When it vanishes, experienced paddlers shrug: You just have to get back in the pool. Keep working. It’ll come back. And in the meantime, if you flip, just get out of the boat. Then get back in.

Maybe that’s why I love kayaking even more than skiing. Skiing was given to me—shaped by family, geography. But kayaking—I chose. And in choosing it now, as an adult, I reclaim something I didn’t have words for at fifteen. Capsizing a kayak teaches you that being upside down isn’t failure. It’s part of history’s rhythm, both personal and national. Sometimes you rise. Sometimes you swim. Either way, you survive. You get back in the boat.