Powder Power

There was a time when Colorado winters began in October. In the last millennium, blizzards came with tempestuous regularity. Her cycle was almost as predictable as mine. You could feel her gathering herself in the a sunset or sunrise before bursting through atmosphere, unannounced yet not unexpected. She was often nocturnal. Furious, fast-moving, and deep. In the morning, we’d wake to bluebird skies, powder glittering in sunlight, refracting through a million tiny prisms.

In my neighborhood, each household marked the first snowstorm as a kind of ceremony. Traditions ranged from removing the spoons from beneath pillows to shovel the morning’s cereal victoriously, to cursing the snow blower empty of oil since April, to rushing the streets in flip-fliops to skate around the unplowed asphalt. I remember being little, burrowed in my duvet like a vole in the subnivean zone, and listening for the grumbles of the plows as they caused my petal-pink curtains to tremble slightly. Cadence was everything. Each scrape told a story of accumulation: shimmer rising from ankle to calf to thigh.

We’d listen for the tunnel closure on the AM radio, and the snow guns sat idle, mocked as a sign of failure—a last resort. Winter was herself, extant. Obvious as the summer scorch that sent us kids scrambling and unsupervised into the creeks in dubious inner tubes to cool off in the last of her surge. The creeks gave us a lifeline to the snow, year-round. The peaks wore their white uninterrupted. Veils that came down to the valley's hips, like royal brides. We believed winter could take care of herself. And she did.

But now, she arrives hesitantly in November. The snow holds memory the way the land does: in layers. Read it carefully.

Last year, the early-season ground cracked open under too many cloudless days. The snowpack, what little there was, grew from the bottom up—thin, faceted crystals forming in the depth hoar layer like rot beneath an unrenovated floor. My ski school colleagues and I watched our first students skid down Springmeier, scraping the treacherous white ribbon for tenuous slivers of joy. By Christmas week, C., one of my favorites returned. She comes up from Texas twice a year and wears a red jacket that makes her sing out against the high alpine white like a cardinal. Bald fields of rock and stern patrol ropes barred her from her favorite haunts. Disappointed, she made the most of the terrain we had open, but soon slipped into boredom. She surveyed the sad state of the bump runs below E Chair and sighed.

“Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow…” C. sang, mostly to herself. But the atmosphere heard her. A handshake of flurries answered.

On the next lap, she sang again. Again, the atmosphere shimmered in reply. The following day, the same miracle occurred. C. would sing, and the sky would wink with snow. Clearly, we decided, this is no coincidence. We promptly began weaving a mythology: part Norse myth, part Disney. Ullr, god of snow, had been stolen away. Elsa, snow-singer and queen of frost, wandered the peaks calling him back. Their reunion, we believed, would bring the storm.

We never named the villain.

So far, this season has threatened to echo the last. It is February, and anemic snowfall, freeze-thaw cycles, and long, dry spells gnaw at what little base we have. Weak layers fester in the snowpack—depth hoar beneath crusts of melt and refreeze, a recipe for instability. South-facing slopes reveal brush and talus well into January. The crowd-weary mountains wear their bones.

Then, Presidents’ Weekend, and with it, the shift. The sky darkened. From her home far away in Texas, Elsa must have sang, setting Ullr free. Three days of heavy squall followed—warm, wet, and wind-lashed. For the first time this season, the stake measured in feet. But it came with weight. It laid down heavy, rimed with supercooled water droplets. Wind loading sculpted slabs, compressed grains, and packed in the density. This was not the champagne powder untracked through my memories of childhood—it was Sierra cement dropped onto a fragile Rocky Mountain base.

Still, we rejoiced. Riders poured down chutes and bowls, churning through the stick, their exhalations rising in clouds. It was not easy skiing, but it was skiing. Across the mountain, laughter flung itself off ridgelines, filtering through glades of spruce and fir. My client and I spent the weekend ducking into tree lines, searching for preserved stashes hidden from sun and wind. On Monday, we skied out over a series of ridges linking Way Out to Double Barrel, beneath the still roped-off Snow White. And there, we finally found it: a few turns of soft untouched—shaded, crisp, and preserved beneath the surface crust. The promised powder of my memory, many Colorado-goers’ dreams. We lapped it three times, delighting in the cohesion of storm snow undisturbed, our turns arching across the slope like calligraphy on parchment.

“Grandmother’s House,” we started calling it.

On our final run, we stopped to rest. A lone skier had also come over the ridge and through the woods. He stood above us, in the heart of Grandmother’s House, eyeing a jump he’d sculpted.

“How’s the landing?” he called down.

“Stable!” we yelled back. “But hold up—we’re in the fall line.”

He waited. We got out of his way. From below, we watched him send a front flip, landing low and deep, his hips brushing the snow but holding. When he rose, he was grinning.

“That’s my jump,” he announced. “Built it myself.” Then he eyed the logo on my coat. “Don’t tell patrol.”

“Don’t worry. I won’t.”

These are the stories that accumulate on powder days like layers in the snowpack. Joy on joy. Storm on storm. Weakness beneath strength. The metaphor, like the snow itself, is stratified. We love powder for its freedom—for the way it unweights the body and quiets the mind. But we must also love it for its truth: what is beautiful is often fleeting.

Childhood visits to Grandmother’s House suspend in the snowglobes of nostalgia because they are brief. But like Grandma—or Ullr—these delights can and will vanish from our sights permanently. This is not the scarcity that breeds preciousness. It is obliteration’s Sword of Damocles. We must speak plainly now: the kidnapper in C’s story is no villain from myth. It is us. Our carelessness, our carbon, our forgetting. The vanishing snowpack is not just the inconvenience of subpar meteorologists or an ignomious Mother Nature—it is science written in crystal and melt.

Avalanche forecasters read the snow like scripture: each storm a sentence, each crust a caution. Surface hoar buried by storm snow is a velvet snare. A warm dump atop cold facets—a house built on marbles. They teach us that we must test what we see. We must listen. Then dig. The title of Robert McFarlane’s new book asks. “Is A River Alive?” If the answer is an unqualified yes, then the mountains whose spring runoff gives birth to the rivers and feeds them must also be thought of as alive. The snowpack speaks to those willing to learn its language. And right now, the snow is alerting us to the same dire sickness afflicting its offspring, the rivers, streams, and creeks. If the rivers are dying, so is the snow.

If skiers want Ullr to give us more lifetimes of winters—if we want snowfall to outlive us, to be bequeathed to our children—we must save Grandmother’s House. This means moving beyond song and into action. Stewardship is the chorus that must follow awe. Protecting the state and national forests, the lands borrowed by our resorts. Pulling back on snowmaking to protect energy and water reserves, even if that means shortening the extended season we’ve come to believe we’re entitled to.

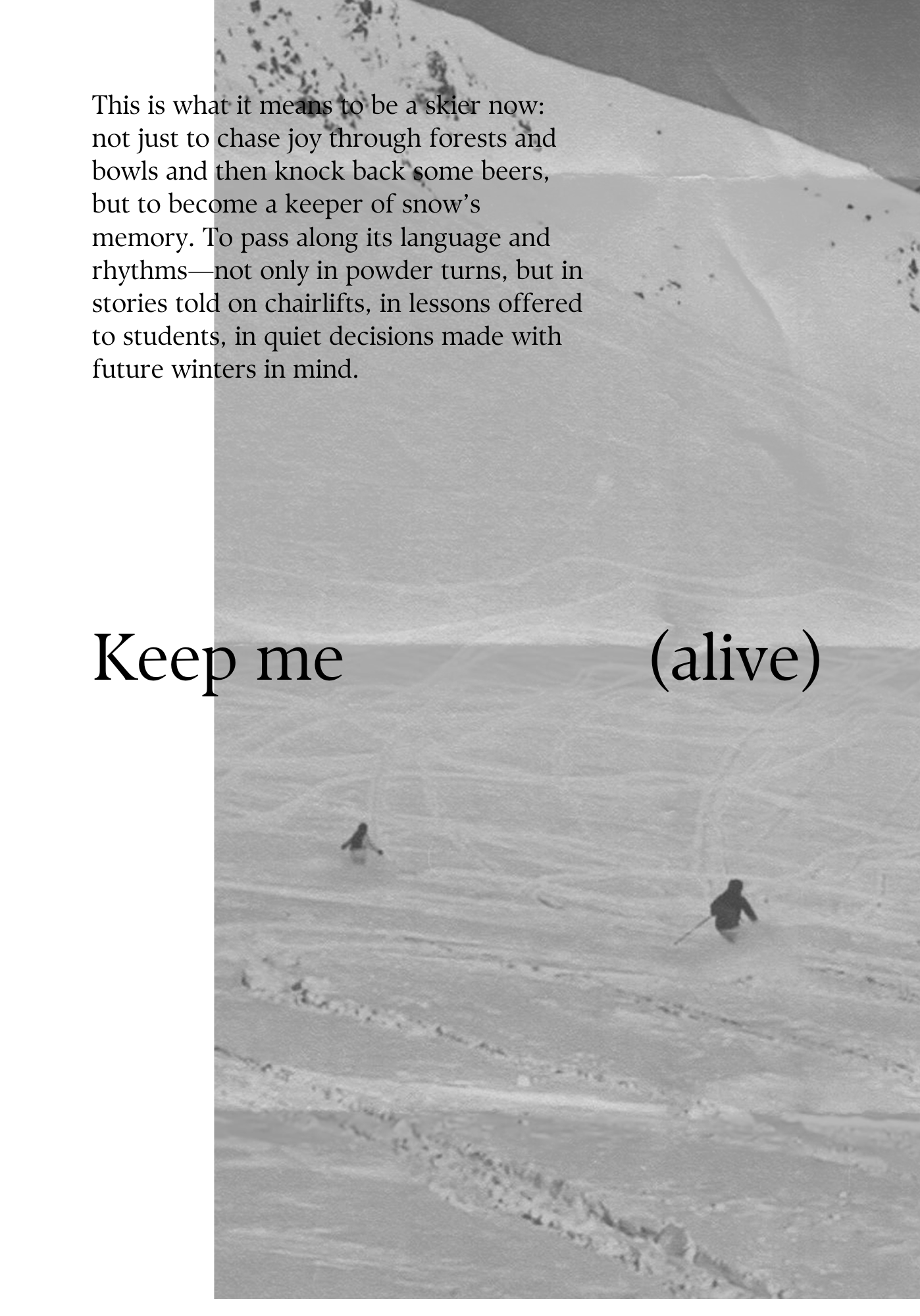

To protect winter is to protect a way of knowing who we are on this Earth: track-makers, storm-chasers, feet-counters—temporary accumulations as interconnected as the snow itself. This is what it means to be a skier now: not just to chase joy through forests and bowls and then knock back some beers, but to become a keeper of snow’s memory. To pass along its language and rhythms—not only in powder turns, but in stories told on chairlifts, in lessons offered to students, in quiet decisions made with future winters in mind. And when the dry spells stretch longer, which they will, we must not despair. We must not abandon the mountains and accept as inevitable the artificial snow domes of places like New Jersey and Dubai. Winter will always know how to make more snow when the conditions, meaning us, allow her to. So long as, somewhere, a lone cardinal sings of the dream of winter, there is always hope. Let it snow.