The Snowy Egret

The three women arrive for the sunset tour half an hour early. The July sun still hangs high above Boothbay Harbor, layering its honeyed heat on the backs of lobstermen hauling traps and tourists cradling cocktails in the shade of balcony bars. The tide is at its lowest ebb—minus nine feet—exposing every rock and wrinkle of our corner of the harbor. Rockweed glistens across the mudflats like towel-dried hair. And there, poised in the pause, stands a snowy egret—slender, pale, and still. She lifts each foot slowly, delicately, as if stepping through time itself.

Long ago, herons and egrets were said to be messengers of Athena—the goddess of wisdom and watchfulness. They appear to alert us to moments that matter.

I begin the ritual of readiness: PFDs—check. Paddles—check. Sunscreen, water—check, check. We gather before the nautical chart nailed to the emerald-shingled wall of the shop. I show the women where we’ll go. They tell me where they’re from.

“Minnesota,” they say. “We kayak a lot on the lake back home, but never on the ocean…”

A mother and her two daughters, somewhere in their forties. Older than me, but not by much. I give the safety talk, then we head to the dock—across the 1901 footbridge and down to the floating Carefree Dock launch. The gulls—herring and laughing—circle above, loud and bright. But the egret remains unperturbed, combing for her dinner, quiet as a held breath.

I kneel on the dock, warm wood pressing into my knees. I outfit the younger daughter first, snug in her orange-and-red Old Town. Then I turn to her sister.

“We’re not launching from here, are we?” she asks, glancing at the water, the edge, the need to lower the kayak sideways and climb in.

“Yep,” I reply. “That’s the plan.”

“I can’t do that. I have a rod in my knee. I can’t crouch. I can only launch from a beach.”

I blink—surprised. In all my supposedly careful prep, I’ve forgotten to ask the essential guide question: Is there anything I should know?

The beach launch unfolds slowly, improvised. It’s nearly seven now, and the rental staff have long since gone home. I haul three singles to the harbor floor myself, boats balanced awkwardly on my shoulders. The tide has stripped the sea back to its bones. A narrow track of pebbles winds through the rockweed and slippered stone. The footing is treacherous, especially for the mother, whose hand I take in mine. Together, we move like tidepool creatures—careful, deliberate. On the far side of the cove now, the egret steps with us, patient and silent.

I launch the younger daughter first. Then the mother. And then I’m alone with the sister—the one whose knee is threaded with steel. Together, we lower her into the cockpit. Sweat slides down my spine. My legs are trembling. Their early arrival has become a late departure. I wonder if I’ve already failed them.

But when I look down, she’s smiling.

“Thank you for all this extra effort,” she says, and sighs. “I have breast cancer. It spread to my bones. That’s why the rod. The surgery was last year. This trip is part of my bucket list. I grew up kayaking lakes, but I’ve never been on the ocean. I wanted to see the sunset over the sea.”

I nod, and she lifts her hand for a high five. There is nothing else to say. Even the gulls are quiet now.

A few winters ago, 10,000 feet above the sea, I guided another trio—another mother with two daughters. This time in snow, not salt. The Breckenridge mornings were sharp and dry, snow crystals squeaking under our boots, the air so cold it scraped our lungs. They spoke in soft Southern cadences, but skied like they were born in the Northeast—tight stances, fast edges. They loved the bulletproof groomers of Peak 10, but like most who came to Women’s Camp, they’d ticked the challenge me box.

So I took them higher.

Up into the high alpine, where wind scours the cornices and the spruce give way to stone. Horseshoe Bowl. Then Imperial. There, in the ruggedness of it all, they softened. Their carving gave way to something quieter. They stopped muscling the mountain and started listening to it instead.

On the final day, we dropped into Whale’s Tail. The mother led—elegant, measured. Then her skis found a seam of wind-crusted snow. Her weight shifted. She tumbled—head over heels, arms and poles and powder in all directions.

She came to rest upright, blinking. Her daughters saw the fall and forgot their fear. They cut their lines and skied straight to her like ospreys diving for a fish. When they reached her, the panic on their faces was raw. She laughed and reached out, took both their hands.

Later, I rode the old double chair with the mother—just the two of us, inching past a porcupine tucked into a shaggy spruce.

“You’ve asked me ten times if I’m alright,” she said, grinning. “Now I have to tell you something. Thank you for taking me up there. Thank you for the fall.”

She turned her face toward the wind-scoured ridge.

“I have stage 4 cancer. I’m not supposed to be here. If my doctor knew—I’d be in trouble. But trouble’s who I am. I didn’t want any special treatment. I just wanted to ski. And you showed me I still can. Not just the easy runs. All of it. The steeps. The wild. The unknown. It’s good for my daughters to see me push. Even more so to see me fall.”

“Nobody gets out of here without suffering,” a grief counselor in Manhattan once told me. “It’s part of the deal.”

But so is immensity.

The vastness of the world and us in it, that just is. A horizon doesn’t fix anything—it simply makes space for all that can’t be said. So do the treeless crowns of mountains. The unbroken blue beyond the harbor mouth. Places where clinics shrink to specks, and even love—steady as it is—is relieved of carrying the weight alone.

To be alone together in such places is to feel ourselves become islands—separate, aching—but still part of a chain. As Donne once wrote: not of the main. No man may be an island, but a woman—mothers and daughters, especially—most certainly may be. And her experience of illness may be isolated in interdependence. Archipelago or island, nature furnishes solitude with witness. And witnessing—the fall, the rise, the shimmer of a snowy egret against the harbor mud—is life.

Back in Boothbay, it’s nearly eight. The clouds are multiplying now. Wildlife keeps its secrets. No seals. No porpoises. Only the hush of paddles in water. We round Tumbler Island—a humped rock crowned with a weathered Cape-style home—and then the sky opens.

The sun pours through like revelation, gilding the pine-lined shore and scattering petals of light across the sea. The water burns marigold, then poppy, then rose. It is no longer water, but a floating field of wildflowers.

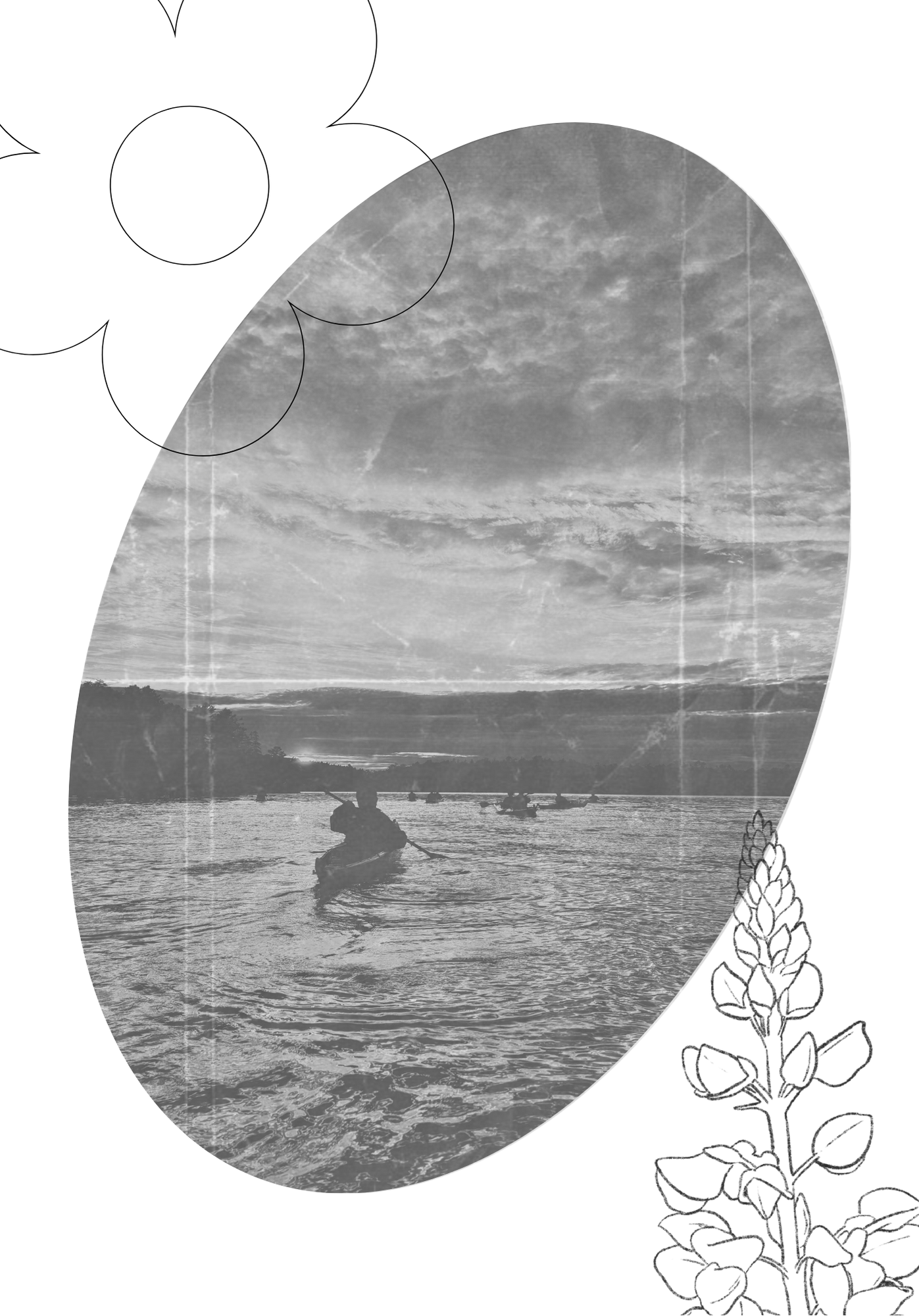

The women drift near, yet apart. The current has shifted; it is now carrying us home. The mother and younger daughter flank the eldest, whose kayak glides alone. Her bow points due west as she drifts until the sun aligns with her. For a moment, she is absorbed by it. Then she reemerges—only silhouette, haloed, held in the palm of the dying light.

We watch her. No one speaks. Not even the wind.

When we return to the beach, the light on the harbor has turned to lavender. The lobstermen are home and showered. On the deck of the Lobster Wharf, a man with a guitar strums Sweet Caroline.

I help the three women out of their boats, then carry each one back up. When I go to lock the shop, I glance through the dark toward the flooding mudflat.

The egret is gone.