On HABs

Shoulder season means coming home to the Catskills, where an ancient, tidally breathing estuary waits at the foot of these hills. The whole way down I-95 from Maine with my salt-streaked Delphin snake-strapped to the roof, I’m eager for warm, familiar brackish where I’ve slalomed bow-draws through waterlilies that raft in the back-eddies. But before I can even unload the car, a warning from local paddlers lands in my inbox: HABs—harmful algal blooms—on the Hudson. Kingston Point Beach is closed.

The Hudson is my homewaters. The river has saddle-stitched the chapters of my life; if the last decades have a spine, it is the river’s. Before I was a paddler, she was a boundary layer I barely perceived—an urban wind tunnel in winter, a summer fringe to the High Line, a moat separating “the center of the world” from its antithesis, New Jersey. Then Covid redrew the isobars of my life. I crossed the George Washington Bridge, followed the estuarine gradient upstream, and settled in the headwater hills the river once carved with ice.

Three summers ago, the Hudson became my kayak nursery and classroom: first strokes and wet exits, rescues practiced in green-brown chop, the path that led to my instructor cert with Hudson River Expeditions. My first overnight as a sea kayaker—a seventy-mile, four-day descent from Poughkeepsie to New York—felt like traveling a trophic and cultural cline, the ebb pulling us beneath bridges like beads: Mid-Hudson, Newburgh-Beacon, Bear Mountain, the re-christened Mario Cuomo, and at last the little red lighthouse tucked under the George Washington. To paddle my way back into midtown was to tie off a transition between life eras with a tidy bowline: from city-bound writer to outdoor professional, strung along a single body of water.

Email notice from kayaking the liquid skies (9/25/25).

“The Hudson was once a cesspool of filth,” the history-buff kayakers like to remind you. “For centuries, people dumped all kinds of crap here—dioxins, pesticides, raw sewage. Indian Point left its mark, and GE, worst of all, poisoned whole reaches with PCBs. The cleanup only began in the 1970s. Amazing we can even paddle here now.”

The worst outbreak of blooms in 40 years inscribe the present tense in a scientist’s lexicon. Cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton—neither fish nor tree—are photosynthesizers catalogued by color and clade: green, red, brown; diatoms, dinoflagellates, blue-greens. In balance, they underwrite primary productivity, turning light into living carbon. But increase nutrient loading—sewage, lawn runoff, manure; warm the water; slow the flushing—and eutrophication takes hold. Pigments slick the surface like spilled paint. Some blooms merely shade; some produce toxins. All are a message in dissolved oxygen and turbidity: choke the light, starve the gills, tilt the river toward hypoxia. Longer heat stretches stratification; drought reduces turnover; nutrients light the fuse.

It’s not just the Hudson, either. In Maine, they warned me of “red tide.” After heavy rainfall, shellfish become suspect. While clams and mussels can purge in days or weeks, oysters bioaccumulate and hold toxins like childhood memories.

Our first weekend back, we drive to Cornwall to meet my paddling buddy, who calls himself the Wolf—seventy-seven Augusts and counting, a gold hoop and a turkey feather tucked in his hatband. “Talismans,” he calls ‘em, to sanctify his new status as a kayak guide. Before he ever got the gig, he guided me. We met unloading the same boat, Alchemy Daggers, at Kingston Point (the beach now closed) and have paddled together ever since. From Rhode Island to Alaska, the Wolf’s hand-of-godded and towed me out of trouble more times than I care to admit.

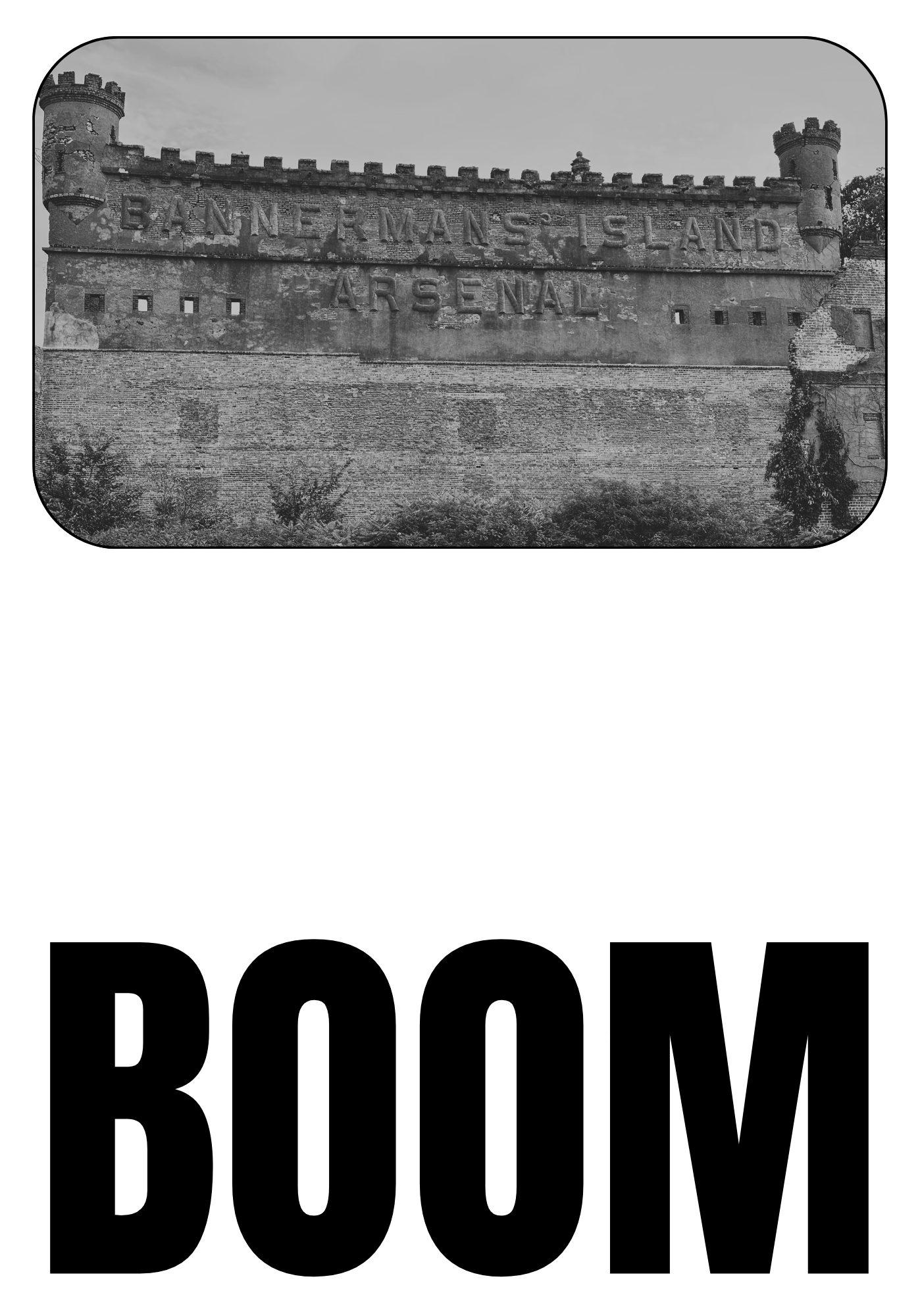

This summer, he’s been leading trips Bannerman Castle, the eccentric ruin on Pollepel Island. The HAB index down here isn’t high enough to cancel tours, so he launches our group in the shallows and waves us off the barge wake. Little green dots whirl off my paddle like confetti. A spotted lanternfly touches down on my hat brim—cryptic gray forewings, sudden aposematic red beneath.

“Kill it,” the Wolf says, soft but absolute. “Slowly, if you can, to send a message to the others. They’re very invasive.”

Maine’s erratic lobstermen and postcard beaches give way to New York’s working waterway. Here, paddlers thread wake, wind, and weekend barges. City etiquette seeps upstream—sidewalk habits translated to current and channel. Down here, people are used to people: they dodge, shift, merge. The tour crowd changes, too—New Yorkers, kin to New Englanders, but tempered: grittier, somehow sleeker. A Women’s History professor from Albany tells me why she drove her family three hours downriver to kayak today: “History,” she says. “What else?”

We cross on slackening flood and scramble over the rocky landing, slick with periphyton. The Hudson doesn’t swing ten feet like Maine waters, but its three-foot tide still breathes diurnally through this fjorded valley. A guide in a BANNERMAN’S CASTLE shirt with a Long Island lilt gathers us by Mrs. Bannerman’s pie garden. The Wolf hangs back, chewing the inside of his cheek. He knows the script; the island’s story is an American geomorphology of ambition and decay.

“In 1900,” the guide begins, “a Scottish immigrant named Francis Bannerman VI purchased this rock and began building what he called his Arsenal…”

“He was the country’s original arms dealer,” the Wolf whispers, shading the official story. “Ran the biggest military surplus operation that became the Army Navy Surplus Store. This place is an adult game of hide-and-seek.”

The guide confirms the Wolf’s footnote: after the Spanish–American War, Bannerman bought 90% of the US military’s unused weapons, uniforms, and black powder—so much that Brooklyn officials blanched at the thought of his munitions next door to the naval yard. The baron desired storage and spectacle, so he doodled himself a castle—part Scottish baronial, part billboard—its crenellations spelling BANNERMAN’S ISLAND ARSENAL for every passing steamboat to read. Poured quick and cheap, the concrete fairy-tale went up quick. For a time, it advertised a fast-tracked empire.

Then came the classic Gilded Age parabola: the warehouse exploded in 1920, Bannerman followed soon after, and the slow unspooling began. In 1969, fire set the period at the end of the sentence. What’s left is a buttressed rib cage open to weather, a shell that now stages local theater and a ruin Metro-North commuters know by heart—an almost uncanny echo of The Great Gatsby’s closing line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Last year, when my recovery from surgery kept us in the Catskills longer than planned, J. became one of those commuters. Three times a week he watched the ruin drift past his train window and wondered, What is that place? Now, circling the bones of its drawbridge by kayak, he carries the gleam of a boy in his first European dungeon. Pattern recognition fires.

“It’s like the AI bros of today,” he muses, and the history professor chuckles. “All in on a good idea, no training or foresight. Hoard the tech, ignore the regs that are coming, pretend obsolescence won’t arrive. I call it the ‘let’s-build-a-fort’ mentality. That’s what this Bannerman dude did—and look what happened.”

“Spot on,” she replies. “Everything that’s happening now is not unprecedented. Only question is: what’s your role in all this going to be?”

The Wolf’s role is clear.

“Four o’clock!” he cries. “Time to go!”

His bow edges out, turkey feather an exclamation point. The historian tracks his line across the channel toward the take-out, reading the microcurrents by the feather. Green freckles wink in our wakes. She flicks a lanternfly from her shoulder; it pinwheels on the miso-colored surface. J.’s comparison lingers. If Bannerman’s boom is a parable for our extractive cycles, the HABs are nature’s bots: cellular networks that, in low abundance, the system metabolizes—but with heat, stagnation, and feed, they scale into systemic risk. Lethal for pets and harmful to humans.

Was it just last October the Wolf and I practiced rescues and rolls a few miles upriver from here? Contamination isn’t dramatic; it’s steady—like sedimentation, a floodplain filling grain by grain. To get rid of the HABs, as the Columbia Riverkeeper says, the task is none other than tackling climate change itself: “…we need to reduce nutrient inputs from industrial chemicals, fertilizers, manure, and human waste; increase water flow; address the temperature impacts of dams; and curb climate change.”

While small efforts from individuals can always help, like picking up pet waste, the true remedy is for it all just to stop. Then wait for as long as it takes for the water to clean itself. But once the bloom is here, there’s little that can be done. Don’t swim in the waters, keep the dog away, and, in time, maybe it’ll dissipate.

“For time is the essential ingredient,” writes Rachel Carson in Silent Spring; “but in the modern world there is no time.”

The next day, J. and I head to the Hudson Valley Garlic Festival. Eighty degrees in late September. Saugerties is a mosaic of garlic hats, witches, vampires, and soil-rich hands. In the hay-bale commons, the Arm-of-the-Sea Theater unfurls a puppet river in cerulean silks and sings a song about photosynthesis to a chorus of equally delighted adults and kids. The troupe’s mission—“handmade theater as an antidote to ubiquitous electronic media and consumer culture”—ripples through the crowd as boos meet the colonial realtor and cheers rise for hemlock, oak, and pine. Some of us are locals; some are not. Everyone is listening. For the finale, the bear waddles onstage with a kayak cinched around his belly, paddle in paw. He dips the blades into imagined current, singing of environmental resilience to papier-mâché trout and city transplants alike.

Tucked in the generous allium bounty of small farms, the play reminds me the Hudson holds more than ruin and warning. Time may be short; creativity is not. Hope here is granular—plankton-small, stitch by stitch—gathering in community theater, in a professor’s silent paddle cadence, in the turkey feather on a 77-year-old guide’s hat.

As kayak guides, we lead people into many waters. In Maine we sell clarity—porpoises and ledge ecology, tidal respiration you can feel in your bones. We point to eiders surfing swell, pull out lobster gauges, and say, look how well the world keeps working. It’s easy to forget that Rachel Carson spent her summers on Southport Island, just across the bridge from Boothbay Harbor where I lived this season—and that her time there shaped the work that helped end DDT’s reign. Without her, the islands where I taught Leave No Trace and delighted in shorebird abundance might have read differently. As the history professor reminded us: none of this is unprecedented. The bots aren’t new tech. They’re just the same old contaminants in a new form. Throughout human history, they’ve appeared, amassed, attacked—and they’ve been diluted, diffused, and defeated.

On the Hudson, the lesson isn’t so different. The Wolf threads us through the arteries of an overbuilt watershed to a Gilded-Age folly between interstate bridges. Here the riparian speaks in closures and neon veils, but also in the older key of resilience and succession: flood-pulse, leaf-drop, Forever Wild. On the banks, a countercurrent steadily gathers—garlic-fest crowds, hay-bale audiences, a bear in a cardboard kayak. Creativity is the Hudson Valley’s unique civic hydrology: it braids strangers, slows the current of despair, and makes room for oxygen. The river remembers how to heal. We must remember how to belong.